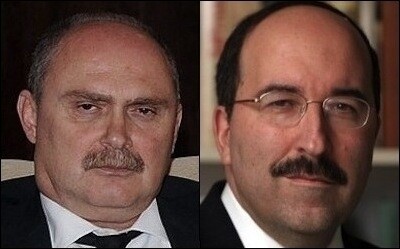

Israeli Foreign Ministry Director-General Dore Gold (right) reportedly met secretly in Rome with Turkey’s top career diplomat, Foreign Ministry Undersecretary Feridun Sinirlioglu (left). |

For Turkey’s Islamist government, breaking up with Israel, a credible regional ally until 2009, was a calculated move. Then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s famous Davos tirade against Israel’s then President Shimon Peres was the beginning of Turkey’s willing road accident with the Jewish state: a systematic campaign based on anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic rhetoric and action that would capture votes at home and help Turkey powerfully emerge with its neo-Ottoman ambitions on the Arab Street. It did, leaving no appetite in Ankara for détente -- at least, until June 7, 2015.

When the Turks went to the ballot box on June 7, they did not know that the way they voted would not only deprive the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) of its parliamentary majority for the first time since 2002, but that it could also forcefully remind the government that it might be about time to revise its nearly bankrupt foreign policy, including relations with Israel.

On June 6, a détente with Israel was virtually an impossibility. On June 8, it was only “unlikely.” Next month, depending on how coalition negotiations shape up, it may be a “possibility.”

Détente with Israel was virtually an impossibility on June 6.

Unsurprisingly, the Israeli press reported that Israel’s Foreign Ministry Director-General Dore Gold held a secret meeting in Rome with Turkey’s top career diplomat, Foreign Ministry Undersecretary Feridun Sinirlioglu, who was Turkey’s ambassador to Israel between 2002 and 2007.

As of June 23, neither Jerusalem nor Ankara denied that such a meeting took place.

On June 24, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu confirmed ongoing talks with Israel, aimed at reaching some form of rapprochement, while suggesting that undue emphasis should not be placed on the gatherings.

That is a good sign, but not enough for premature optimism. “The conventional wisdom in Jerusalem is that such a reconciliation, and a true normalization of ties between the two countries, will be extremely difficult as long as Erdogan is in power in Turkey,” according to a report in the Jerusalem Post. Maybe.

But much less difficult is the scenario in which Erdogan keeps on pulling the strings as he wishes and gains from his ideologically inherent anti-Zionism (he once said that Zionism was a crime against humanity).

The parallel election campaigns of Erdogan and his prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, before June 7, were not different than in previous years: Pledges of solidarity with “our Palestinian brothers” and “prayers at the al-Quds mosque in the Palestinian capital Quds [Jerusalem].” For the first time since 2002, their “we’ll-conquer-Quds” promises at election rallies did not increase AKP’s votes; in fact, the party fell from nearly 50% in parliamentary elections in 2011 to 41%, and lost its parliamentary majority. So, the anti-Israeli rhetoric market for the AKP may have come to its saturation point.

Any potential coalition partner of the AKP will insist on a major foreign policy recalibration.

Erdogan’s -- and Davutoglu’s -- party must, if it wants to stay in power, reluctantly ally with an opposition party. Any potential coalition partner will, among other contested domestic issues, insist on a major recalibration of Turkey’s foreign policy, with Syria on the forefront. A coalition deal, especially with the main opposition (social democrat) Republican People’s Party (CHP) would prune the AKP’s neo-Ottoman regional ambitions and soften its radically anti-Israel policy.

This does not mean that a reconciliation between Turkey and Israel is likely. On the contrary, the odds are probably still against it. But if there is going to be reconciliation between former allies, now may be the time to lay its foundation.

Any potential Israeli mistrust is perfectly understandable. There has been too much bad blood over the past few years to dictate optimism. And neither Erdogan nor Davutoglu has changed their minds about Israel or the “bloody Jooos.” It is only that, in domestic politics, the circumstances have changed.

If there is going to be reconciliation, now may be the time to lay its foundation.

Optimism can be a foolish expectation. But relative, extra cautious optimism would not be too foolish.

Before June 7, Turkey was split (and deeply polarized) along a 50% vs. 50% political fault line. Now it is split (and deeply polarized) along a 40% vs. 60% political fault line -- against Messrs. Erdogan and Davutoglu. The ten percentage point shift is not unimportant in a parliamentary calculus, where even one more (or less) seat is vitally important for the AKP. At times like this, the seemingly “saturated” Israel-bashing market is no longer as existential for the AKP as it was before.

If the meeting between Gold and Sinirlioglu really took place, it was not the first of its kind. Yet it has a symbolic value. Sinirlioglu, a career diplomat, happens to be one of Erdogan’s most senior confidantes – a smart diplomat with no Islamist sentiments.

If the terribly destroyed fences between Ankara and Jerusalem are to be mended, this is a good time to start the work.

Burak Bekdil, based in Ankara, is a columnist for the Turkish daily Hürriyet and a fellow at the Middle East Forum.