Ayatollah Javadi Amoli (left) meets with Mikhail Gorbachev, January 1988. The Iranian delegation delivered a personal letter from Iran’s Khomeini urging the Soviet leader to consider Islam as an alternative to communism. |

Analysis of Iranian activities since 1979 has been plagued first and foremost by the misperception that the system established by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was ever meant to be limited to Iran. In fact, once conquered by the ayatollahs, Iran became a weaponized theocracy that rejects the idea of the nation-state and serves as the vanguard of an Islamic juggernaut to replace all nation-states with a worldwide community of believers (umma).[1]

Khomeini’s system and conduct can best be understood as a Soviet Union in Islamic garb. Analyzing the Islamic Republic’s activities through the lens of Soviet imperialism is not only useful for its parallels—from its Islamic Comintern to its use of “united fronts” for political subversion and conquest—but also because it is the Soviet-Iranian competitive cooperation of the 1980s, which transformed into a Russo-Iranian strategic alliance in the 1990s, that accounts for much of the revolution’s success in metastasizing. And while the revolution may adjust its military and political levers to the vicissitudes in regional and global affairs, its overriding goal remains uncompromising and immutable. In Khomeini’s words:

The Iranian revolution is not exclusively that of Iran, because Islam does not belong to any particular people ... We will export our revolution throughout the world because it is an Islamic revolution. The struggle will continue until the calls “there is no god but Allah and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah” are echoed all over the world.[2]

Where It Began

The Islamic Revolution’s slogan, “Neither East nor West,” indicating non-alignment during the Cold War, is a historic misnomer to describe Khomeini’s relations with the Soviet Union. Analysts and historians tend to emphasize Iranian paranoia over Moscow’s intentions since imperial Russia conquered and annexed parts of Persia while the Soviet Union occupied parts of the country in the 1940s and continued to subvert Iran through the Iranian Tudeh communist party.[3]

The Islamist regime has maintained a deep warmth for Russia, especially after 1988.

However, in reality, the Islamist regime has maintained a deep warmth for Russia, especially after 1988. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was the only foreign leader ever to receive a personal letter from Khomeini (in 1989) urging him to consider Islam an alternative given the imminent collapse of communism.[4] This bond has extended to the relationship between Khomeini’s successor, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, and Russian president Vladimir Putin.[5] While the current relationship is a strategic alliance, the Soviet-Khomeini relationship was more akin to the Russo-Turkish alliance of today, in which their highest mutual priority—the destruction of U.S. influence—allowed them to compartmentalize irreconcilable ideological and geopolitical differences.

The most extreme example of this is Afghanistan where Khomeini and Moscow came to an arrangement whereby Tehran could replicate its Islamic theocracy in Hazarajat, the area predominantly populated by the Hazara Shiite minority while the Soviets shored up their communist state in the rest of Afghanistan. This agreement resulted in the Khomeini-instigated Shiite civil war in Hazarajat (1982-84), in which preexisting religious groups from Najaf and Iran operating under various names, including Hezbollah, Nasr, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC)—Tehran’s foremost domestic control apparatus and foreign intervention tool—infiltrated and took over the region.[6] This occurred despite severe tensions over the Iran-Iraq war and the IRGC’s kidnapping of four Soviet diplomats in Lebanon, one of whom was murdered.[7]

The Soviets and the Iranians would come to an agreement in 1991 in which Tehran would supply the Afghan communist military with fuel in exchange for direct flight connections to Hazarajat.[8] Following the sudden rise of the Taliban, Russia and Iran allied against them and backed the Northern Alliance under Ahmad Shah Massoud.[9] But, following the U.S.-led invasion in 2001, the two countries collaborated on supporting the Taliban, whose then-emir was killed leaving Iran in 2016 after a meeting with Russian leaders.[10]

Internally, the Tudeh became Khomeini’s closest ally in the initial years following the Iranian revolution, supporting all his policies and using its organizational skills to build and staff the Islamic Republic’s administrative apparatus while the KGB itself reportedly helped train the new regime’s security and intelligence services.[11] The purpose of this was ultimately to bring a Soviet-controlled communist regime to power, and Khomeini brutally cracked down to preempt this in 1983, expelling over a dozen KGB agents under diplomatic cover. Yet this arrangement was restored relatively quickly, and Russian intelligence agents returned to help build and train Iran’s feared Ministry of Intelligence and Security in the 1990s.[12]

The clearest demonstration of the Russo-Iranian alliance was their joint intervention in Syria to preserve Bashar Assad’s regime,[13] but their anti-U.S. alliance spans the globe. For instance, when the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) sought Iranian support during the “al-Aqsa Intifada,” it went to Moscow to connect with the IRGC, resulting in the 2002 Karine A affair during which the Palestinian Authority tried to smuggle fifty tons of Iranian-supplied weapons into Gaza in flagrant violation of the Oslo accords.[14]

In the 2000s, Russia helped Iran upgrade Hezbollah’s arsenal via Syria. Pictured above are Iranian anti-tank, rocket-propelled grenade launchers captured by the Israel Defense Forces from Hezbollah, August 2006. |

Russia continues to provide the diplomatic and often military heft and cover to the export of the Islamic Revolution, from Yemen to Syria, to Lebanon, to the Palestinian-controlled territories. In the 2000s, it helped supply and upgrade Hezbollah’s arsenal via Syria,[15] a relationship that has only grown militarily[16] and politically. Russia has also upgraded its relationship with the Islamic Revolution’s proxy in the West Bank and Gaza, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad.[17] Not only do Iran and Hezbollah reportedly use the Russian airbase in Syria for arms deliveries and to protect them from Israeli strikes,[18] but recent reports indicate that Moscow will launch a satellite in the coming months for the IRGC that will dramatically improve its ability to surveil its various battlefronts and enemies.[19] Russia has also reportedly been delivering IRGC-supplied weapons and equipment to Syria since 2015.[20] For some time, Moscow even based heavy bombers on Iranian territory to attack targets in Syria although, once this fact was publicized, the arrangement was brought to an end.[21] Russian bombers are still reportedly allowed to refuel in Iran.[22]

Moscow is capitalizing on Washington’s disengagement to push for a “collective security concept” in the Persian Gulf.

Crucially, Moscow is capitalizing on Washington’s disengagement from the Middle East to push for a “collective security concept” in the Persian Gulf[23] to dovetail with Iran’s Hormuz Peace Initiative (HOPE),[24] which in practice would mean all of Washington’s Arab allies in the gulf would have to kowtow to the IRGC as they progressively lose U.S. support.

Mimicking Soviet Expansionist Strategies

Like Lenin before him, Khomeini initially envisioned a two-pronged strategy of exporting the Islamic Revolution: direct regional conquest coupled with his, by now, well-established Najafi clerical nodes across the Middle East to overthrow their regimes. Thanks to regional and global backing for Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88), Khomeini’s assault was halted in Iraq and the gulf region, but the Islamic Republic’s intent has never wavered: overthrow of the regional regimes and the destruction of Israel.

One of the keys to the Islamic Revolution’s success is the “united front,” the Soviet concept of embedding its communist parties inside ostensibly popular social, political, and military alliances utilizing broad issues around which all segments of society can unite. This could be opposition to a particular leader, anti-Israel and anti-U.S. attitudes, or any other popular grievance. Cocooned within and associated with this broad spectrum of political and social opposition under their barely deniable control, the party could incubate, bind other strands of opposition to it, and, when the time was right, seize total power.

For instance, the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan bound all anti-Taliban opposition to the Islamic Revolution.[25] In Iraq, the 1980s Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) tied the Kurdish opposition to the revolution’s core, and its modern iteration, the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces, has allowed the revolution to control non-IRGC groups even as its political wings have allied with those of Muqtada Sadr, functionally a tool of the revolution, to drive out U.S. forces.[26]

Fighters celebrate the downing of a Saudi plane, Jazan sector, Yemen. The IRGC’s Ansar Allah front will likely become the new tool to overthrow the gulf states once it has solidified its hold on Yemen. |

While its attempts to overthrow the gulf regimes internally or via subversion and invasion have been thwarted to date,[27] the Islamic Republic has succeeded in establishing itself firmly inside Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. The IRGC’s Ansar Allah front will likely become the new tool to overthrow the gulf states once it has solidified its hold on Yemen, a possibility it has openly expressed.[28]

At the same time, Tehran has been forward-deploying its military resources as close to Israel and in as dispersed a fashion as possible. This has meant not only ensuring each front in the region possesses massive arsenals of Iranian missiles, drones, and other armaments, but also establishing local production capability for each front to manufacture its own arsenal. This strategy has also entailed upgrading the precision of these arsenals.[29]

Additionally, the movement has ensured the IRGC components can sustain themselves financially via local economies, organized crime, and other licit and illicit financial schemes so that sustained financial pressure on Iran will not inordinately impact the overall subversive effort. This includes regional and global smuggling networks[30] and other income from the IRGC global crime syndicate[31] and its construction arm, Khatam al-Anbiya and its various infrastructure projects, as well as expansion and maintenance of Shiite shrines in Iraq and Syria.[32]

The IRGC controls the economy of Iraq, siphoning off billions, thus bypassing the sanctions on Iran.

More importantly, the IRGC controls the economy of Iran itself[33] as well as that of Iraq where its “customs-evasion cartel” and control of ministries, ports, and border crossings, including the Baghdad airport, allow it to siphon off billions on top of the “legitimate” funds it receives as part of the state.[34] These funds are then shuffled around to whichever front or fronts are most in need, protecting the IRGC jihad from sanctions pressure on the Iranian economy.

Qassem Soleimani’s “ring of fire” concept of fencing Israel with large, improved missile arsenals on all sides is the penultimate phase of the Islamic Revolution’s strategy. The final phase is the nuclear program, ultimately intended to produce nuclear weapons that can be used offensively, deter external intervention, or negate Israel’s alleged nuclear arsenal, allowing the IRGC to wage a long, exterminationist war of attrition.

Tehran’s Intricate Shell Game

No sooner had the ayatollahs seized power in Iran than they established an Islamic Comintern in Tehran. Colloquially referred to at the time as the Taleghani Center after a revolutionary Shiite cleric, this organization would host all Muslims, Shiite and Sunni, from around the world who had been inspired by the Islamic Revolution and wished to replicate it in their own societies. From these students, Iran formed cadres that would return to their countries and follow its orders in cloning the revolution and conducting terrorist operations, slotting neatly into the global “terrorist international” built by the Soviets and its clients.

In fact, many of the trainers at the Taleghani Center were part of the global Soviet proxy network, including its communist satellites, clients, and Arab protégés, for which Iran would become temporarily responsible during the 1990s while the reborn Russia found its footing. From Libya, Syria, and the erstwhile People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, all the way to Cuba, the Palestinian factions, and North Korea, the Islamic Revolution became a component part of the Soviet “anti-imperialist” nexus. This Islamic Comintern helped create, entrench, expand, or guide terror groups across the gamut and globe.[35]

The roots of this supranational revolution date back to the Iraqi religious center of Najaf, where a multinational group of Shiite clerics formed the revolutionary Islamic Da’wa Party around the time when Khomeini was based in the city.[36] Exiled from Iran in the early 1960s for an abortive Islamic revolution, Khomeini refined and popularized his concept of Islamic government; he built his militant clerical networks and alliances in Iran and across the region while his acolytes from the entire spectrum of the Iranian opposition—Islamists and Marxists to Liberals—were being trained in PLO camps in Lebanon by 1970.[37] This vast depository of revolutionary activity and ideology cross-pollinating in Lebanon, Iran, Syria, and Iraq was ultimately subsumed, co-opted, or destroyed in concentric coups by Khomeini once he officially took power in 1979.

The Iraqi Da’wa Party was a transnational, clerical network laying the groundwork for a regional Shiite revolution.

The Da’wa Party may have been established in Iraq, but it was a transnational clerical network, not an Iraqi organization, and its representatives in Lebanon and throughout the gulf region began laying the groundwork for a simultaneous, regional Shiite revolution to establish a transnational theocracy. The party’s attempted insurrection and terrorism against the Iraqi regime, a prelude to Khomeini’s attempts to create an Islamic state through direct conquest, resulted in the expulsion of tens of thousands of members and sympathizers to Iran.[38] These would become the core of the revolution’s fighters and commanders while the remaining Da’wa clerics in Iraq either moved to Iran or fanned out across the region to help lead sympathizers.[39] These clerics then officially dissolved the Da’wa Party in Lebanon and infiltrated the existing revolutionary Shiite organization, Amal, in order to absorb, subordinate, or destroy it, a process that ultimately resulted in the official formation of Hezbollah in 1982[40] and would be repeated in Iraq in the 2000s with Muqtada Sadr’s Jaysh al-Mahdi.[41]

To illustrate just how indistinguishable these organizations were—from one another and from Iran’s Islamic Republic itself—Hezbollah’s entire leadership, including its spiritual guide Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah, its current secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah, its deputy secretary-general Naim Qassem, as well as former secretaries-general Subhi Tufaili, Raghib Harb, Abbas Musawi, and every other leader were all members of the Da’wa-Najaf network. Harb and Muhammad Baqr as-Sadr, the progenitor of Da’wa in Iraq, worked on the Islamic Republic’s draft constitution in 1979.[42]

Hezbollah—an organizational moniker already in use in Iran in the 1970s under Hadi Ghaffari as well as in Afghanistan, Iraq, and throughout the gulf region in the early 1980s[43]—is merely one of many names the IRGC takes on depending on its location. Hezbollah’s first bombing in Lebanon (in 1981)—claimed under the Da’wa name—was not directed against Israeli, U.S., or French installations but against the Iraqi embassy.[44] Of the suspects in the would-be devastating Kuwait terrorist bombings in 1983, one was a Hezbollah leader and the cousin and brother-in-law of Imad Mughniyeh, Hezbollah’s most infamous terrorist mastermind; another was first cousin to Hussein Musawi, the Da’wa commander of Islamic Amal. Most of the perpetrators, however, were Iraqis still using the Da’wa Party name. These included Jamal Ja’far Muhammad, better known as Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, leader of the Popular Mobilization Forces killed in 2020 alongside his commanding officer Qassem Soleimani, head of the IRGC’s Quds Force.[45] These “Da’wa 17,” arrested after the bombings, would become the cause célèbre and primary justification of Hezbollah’s terrorism.[46]

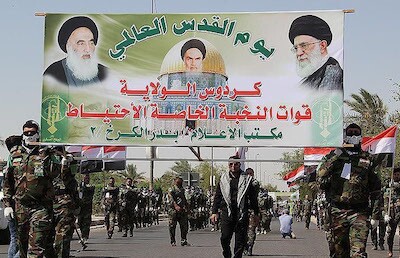

Iraqi militiamen carry a banner depicting Iranian supreme leaders Khomeini and Khamenei. Mischaracterized as proxies and allies, Iran-backed Middle East Shiite militias are organizationally indistinct from the IRGC itself. |

Widely mischaracterized as proxies and allies, the longstanding and proliferating Iran-backed Shiite militias across the Middle East are in fact organizationally indistinct from the IRGC itself. These are not disparate, subordinate, local revolutionary groups allied for a greater cause and supported by the IRGC, but regional names of the same movement with the same leadership and goals that shifts the same personnel and resources to various fronts of its transnational jihad under different aliases.

In Bahrain, this movement has called itself the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain, Bahraini Hezbollah, al-Wefaq, the Islamic Enlightenment Society, and dozens of other political and military front names.[47] In Saudi Arabia, the group named itself the Movement for Vanguards Missionaries, the Islamic Revolution Organization in the Arabian Peninsula (IRO), and Hezbollah al-Hijaz, among others.[48]

In Iraq, this same organization was called, among other names, Hezbollah, the Islamic Action Organization, and Da’wa—all operating within the framework of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq and its armed wing, the Badr corps.[49] This is hardly a comprehensive register of the names the IRGC has called and continues to call itself depending on its location.

Iran-backed Shiite movements across the Middle East are an organic whole with the same leadership, personnel, and aims.

Peeling away the aliases, one finds that all of these alleged movements are just names of an organic whole with the same leadership, personnel, and aims. Muhammad Taqi and Hadi Mudarassi, Abdul Aziz and Muhammad Baqr Hakim, Sheikh Isa Qassem, and others from the multinational Da’wa-Najaf clerical network in Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and even Afghanistan and Pakistan, are all fully beholden to Khomeini and his successors. They were and in some cases remain the men behind this singular movement. Interwoven throughout the region and movement were also Khomeini’s Iranian Shiite clerics from Najaf, men such as the late Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur, a cleric based in Syria who took on the official title of ambassador to Lebanon after the revolution to help run the movement’s Lebanese front.[50]

There is no available evidence that Salah Ahmad Flaytih and Badr ad-Din al-Houthi, the Zaidi Shiite scholars whose sons are the respective spokesperson and leader of Ansar Allah, often called the Houthis, were part of this preexisting Da’wa network. Regardless, they became an immediate extension of the network in 1979, evolving from Flaytih’s and Houthi’s Union of Believing Youth in the 1980s into the Ansar Allah of today, simply another name in the shell game.[51]

There are currently in Iraq and Syria a dizzying array of ever-evolving front groups and orchestrated splits as this Islamic revolution cobbles together or sunders its political and military umbrellas depending on its needs. At times, the movement will peel off the most loyal cadre into smaller, more disciplined military cells while, at others, it will form larger groups for political participation or military activity.[52] Thus, for example, the Iraqi SCIRI and its Badr armed wing have been replaced by the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq[53] while the Badr Organization, Kataib Hezbollah, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, and a myriad other political, military, and social aliases have come under the Popular Mobilization Forces umbrella.

Khomeini’s network has been inextricably intertwined with the Assad dynasty since before the Islamic Revolution.

There is little to be gained from getting embroiled in this shell game given that a core group of the same individuals—including the SCIRI dynasty leadership— oversees all the groups, which share fighters, leaders, operations, and resources. Whatever factionalism and personal rivalries exist, their chain of command, going up to the supreme leader of Iran, is identical, and all are inextricably intertwined with the Lebanese, Syrian, and Iranian fronts of the movement.[54]

In the 1980s, as now, fighters and operatives of all the front groups, arbitrarily categorized by nationality despite pan-Islam’s categorical rejection of such identity, were shifted to various battlefronts of the revolution, primarily Lebanon and Iraq and now Syria. Thus, for example, the Saudi IRO fought in and operated from Lebanon in the 1980s;[55] Iraqi and Afghan front groups fought in Lebanon in the 2000s; and Afghan fronts including Liwa Fatemiyun have been deployed to Iran itself.[56]

This explains why the IRGC’s Quds Force—the sinew tying together the revolution’s fronts—and other IRGC “advisers” are killed fighting inside these groups;[57] why Ansar Allah and the IRGC Iraqi fronts coordinate attacks on Saudi Arabia,[58] and why all of them speak of their local battles as part of the same Islamic revolution.

Where Do Syria and the Palestinians Fit?

IRGC commander Khairollah Samadi (center, in uniform) was killed in fighting in Syria, November 2017. During the Syrian war, the IRGC shifted many of its resources and personnel to defend the Assad regime. |

Khomeini’s network has been inextricably intertwined with the Assad dynasty in Syria since before the Islamic Revolution, and the overall pattern has been one of such close coordination that it is impossible to tell where one ends and the other begins. This is especially true after the Soviet Union, Syria’s patron, collapsed, leaving Damascus unable to sustain its competitive cooperation with the IRGC in Lebanon as it had in the late 1980s.[59] So bound together were the two that Khomeini betrayed the Muslim Brotherhood and supported Hafez Assad’s brutal suppression of the Islamic uprising in Syria, culminating in the destruction of Hama in 1982.[60] Syria has always been the hub and the arm of the Islamic Revolution’s export, which is why current Supreme Leader Khamenei could no more allow Bashar Assad’s regime to collapse than allow his own to fall. The IRGC thus mobilized the entire transnational network, shifting much of its resources and personnel to defend the regime and fully export the revolution into Syria itself,[61] establishing scores of new IRGC fronts woven into the regime’s security fabric and building on its already extensive penetration of the country.[62]

Syria had also been a primary supervisor of Palestinian terrorism and militancy, and while the Islamic Revolution had long been intertwined with the PLO,[63] Tehran took full responsibility for the Palestinians alongside its Syrian client after the Soviet collapse. The revolution has since absorbed the entire political spectrum of Palestinian terrorism, from its direct fronts such as Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) to Hamas and leftist groups; this has been true particularly after Israel exiled hundreds of these groups’ terrorists and leaders to Hezbollah-controlled Lebanon, placing them under the revolution’s control throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[64]

Just how integrated the Palestinian groups are in Khamenei’s transnational jihad was made eminently clear during the May 2021 Gaza war by Hamas’s open gratitude to the supreme leader and the IRGC front groups from Iraq to Yemen, as well as reports of coordinating attacks on Israel.[65] Khamenei himself makes no distinction between Hamas’s leadership and that of the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces, PIJ, Hezbollah, and the IRGC itself when discussing the network’s martyrs.[66] So much so that during a press conference by IRGC Aerospace Forces commander Ali Hajizadeh, Hamas’s flag was included among those of its other fronts.[67] Soleimani is reported to have referred to Hamas and PIJ as two of Iran’s external “armies” in the region.[68]

Conclusion

The collapse of the Soviet Union almost instantly brought down its global client network and communist fronts. Excising the Islamic Revolution from the Iranian state would do the same to its organs throughout the region.

Often dubbed the “resistance axis,” the IRGC is no ordinary national army but the vanguard of a multinational Islamic revolution—a supranational monolith whose nerve center is located in Iran. As such, it is no more Iranian than Hezbollah is Lebanese or Ansar Allah is Yemeni. IRGC indoctrination materials do not mention Iran, and its members are referred to as “mujahedeen"—warriors of God—rather than as Iranian soldiers, as it trains a multitude of local proxies and allies in a fully-integrated, transnational network across the region. Occasional pragmatic feats notwithstanding, the Islamic Republic has never moderated its long-term ambition to substitute a broad theocracy for the existing regional (indeed global) political order.

In this it has been helped by the Soviet Union and now Russia, with which it shares both allies and clients as well as the overarching goal of destroying U.S. influence in the Middle East. Far from a recent partnership of convenience, the Russo-Iranian alliance is ideological and has existed since at least 1989, though even in its infancy the revolution owed much of its power and ideology to the Soviets and their global network. Just as Hezbollah and PIJ/Hamas cannot be compartmentalized as Lebanese or Palestinian issues, so Russia cannot be dealt with as a separate problem from the Islamic Revolution in the Middle East.

Oved Lobel is a policy analyst at the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council.

[1] Kasra Aarabi, “Beyond Borders: The Expansionist Ideology of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps,” Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, London, Feb. 4, 2020.

[2] Efraim Karsh, Islamic Imperialism: A History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 217.

[3] Michael Rubin, “Iran-Russia Relations,” American Enterprise Institute, Washington, D.C., July 1, 2016.

[4] Baqer Moin, Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), pp. 274-5.

[5] Iran International TV (London), Feb. 11, 2021; Reuters, Nov. 1, 2017.

[6] Barnett R. Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), p. 264; Kristian Berg Harpviken, “Political Mobilization among the Hazara of Afghanistan: 1978-1992,” Peace Research Institute, Oslo, 1996.

[7] Pierre Razoux, The Iran-Iraq War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), p. 338.

[8] Rubin, “Iran-Russia Relations,” p. 264.

[9] “Crisis of Impunity: The Role of Pakistan, Russia, and Iran in Fueling the Civil War,” Human Rights Watch, July 2001, pp. 35-45; The New York Times, July 27, 1998.

[10] The New York Times, Aug. 5, 2017.

[11] Carl Anthony Wege, “Iranian Counterintelligence,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 2019, no. 2, pp. 272-94, ftnt. 44; “Defection Hurt Iranian Communists,” Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, D.C.

[12] Oliver Jones, “Iran’s intelligence and security apparatus,” UK Defence Forum, Dec. 2011, p. 6.

[13] Reuters, Oct. 7, 2015.

[14] Yehudit Barsky, “Hizballah: The ‘Party of God,’” American Jewish Committee, New York, May 2003, p. 28.

[15] The New York Times, Aug. 6, 2006; Andrew McGregor, “Hezbollah’s Creative Tactical Use of Anti-Tank Weaponry,” Jamestown Foundation, Washington, D.C., Aug. 15, 2006.

[16] Al-Monitor (Washington, D.C.), Mar. 18, 2021; al-Manar TV (Beirut), Mar. 25, 2021.

[17] The Algemeiner (New York), Aug. 7, 2018.

[18] The Wall Street Journal, Apr. 17, 2018; Rubin, “Iran-Russia Relations,” p. 264.

[19] The Washington Post, June 11, 2021.

[20] Fox News (New York), Oct. 29, 2015.

[21] BBC (London), Aug. 22, 2016.

[22] Anadolu Ajansı Agency (Ankara), Apr. 14, 2018.

[23] TASS News Agency (Moscow), Mar. 9, 2021.

[24] Mehran Haghirian and Luciano Zaccara, “Making sense of HOPE: Can Iran’s Hormuz Peace Endeavor succeed?” Atlantic Council, Washington, D.C., Oct. 3, 2019.

[25] “Crisis of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, pp. 35-40.

[26] The Guardian (London), Jan. 24, 2020.

[27] David Crist, The Twilight War: The Secret History of America’s Thirty-year Conflict with Iran (New York: The Penguin Press, 2012), pp. 262-3, 300-10.

[28]Al-Mayadeen TV (Beirut), Twitter, @AlMayadeenNews, May 30, 2021.

[29] Fabian Hinz, “Missile multinational: Iran’s new approach to missile proliferation,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, Apr. 26, 2021; “Hezbollah’s Precision Missile Project,” BICOM Briefing, Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre, London, Oct. 4, 2019; al-Monitor, May 17, 2021.

[30] “Treasury Sanctions Network Financing Houthi Aggression and Instability in Yemen,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, Washington, D.C., June 10, 2021.

[31] Josh Meyer, “The secret backstory of how Obama let Hezbollah off the hook,” Politico, 2017.

[32] The Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2019; Radio Farda (Prague), July 5, 2020; Reuters, Dec. 2, 2020.

[33] Ahmad Majidyar, “IRGC’s role in Iran’s economy growing with its engineering arm set to execute 40 mega-projects,” Middle East Institute, Washington, D.C., May 7, 2018.

[34] Agence-France Presse, Mar. 29, 2021; The New York Times, July 29, 2020; “A Thousand Hezbollahs: Iraq’s Emerging Militia State,” Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy, Washington, D.C., May 4, 2021.

[35] Robin Wright, Sacred Rage: The Wrath of Militant Islam (London: Andre Deutsch, 1986), pp. 32-5

[36] Rodger Shanahan, “Shi’a Political Development in Iraq: The Case of the Islamic Da’wa Party,” Third World Quarterly, 5 (2004): 943-54.

[37] Afshon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 113-4; Tony Badran, “The Secret History of Hezbollah,” Washington Examiner (D.C.), Nov. 25, 2013.

[38] Razoux, The Iran-Iraq War, pp. 2-4; Crist, The Twilight War, p. 86.

[39] Shanahan, “Shi’a Political Development in Iraq,” p. 949.

[40] Augustus Richard Norton, Hezbollah: A Short History (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2018), p. 20.

[41] Marisa Cochrane, “Iraq Report 12: The Fragmentation of the Sadrist Movement,” Institute for the Study of War, Washington, D.C., Jan. 2009.

[42] Magnus Ranstorp, Hizb’allah in Lebanon: The Politics of the Western Hostage Crisis (New York: Macmillan Press Ltd., 1997), pp. 25-33; Shanahan, “Shi’a Political Development in Iraq,” p. 949.

[43] Barsky, “Hizballah: The ‘Party of God,’” p. 21; Toby Matthiesen, “Hizbullah al-Hijaz: A History of the Most Radical Saudi Shi’a Opposition Group,” The Middle East Journal, Spring 2010, pp. 185-97.

[44] Norton, Hezbollah, p. 59.

[45] The New York Times, Feb. 7, 2007.

[46] Ranstorp, Hizb’allah in Lebanon, pp. 91-3.

[47] Michael Knights and Matthew Levitt, “The Evolution of Shi’a Insurgency in Bahrain,” CTC Sentinel, Combating Terrorism Center, West Point, Jan. 2018, pp. 18-25; “Review of the Islamic Call Party (Hizb al-Da’wa al-Islamiya) in Bahrain—January, 1984,” Defense Intelligence Agency, Washington, D.C., Feb. 19, 1984.

[48] Matthiesen, “Hizbullah al-Hijaz.”

[49] “Iraq’s Exiled Shiite Dissidents,” Central Intelligence Agency, Langley, McLean, Va., June 1985.

[50] Wright, Sacred Rage, p. 35; Ranstorp, Hizb’allah in Lebanon, pp. 79-80

[51] Nadwa Dawsari, “The Houthis and the limits of diplomacy in Yemen,” Middle East Institute, Washington, D.C., May 6, 2021; Abdo Albahesh, “The Relations of Houthis with Iran and Hezbollah,” Yemen Center for Strategic Studies and Researches, @al_bahesh, Nov. 4, 2018; Bruce Riedel, “Who are the Houthis, and why are we at war with them?” The Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., Dec. 18, 2017.

[52] Reuters, Jan. 4, 2020, May 2, 2021.

[53] Phillip Smyth, “Should Iraq’s ISCI Forces Really Be Considered ‘Good Militias’?” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, D.C., Aug. 17, 2016.

[54] “Militia Spotlight: Profiles,” Policy Analysis, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, D.C.; Phillip Smyth, “The Shiite Jihad in Syria and its Regional Effects,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Feb. 2, 2015; Smyth, “Hizballah Cavalcade,” Jihadology.net.

[55] Matthiesen, “Hizbullah al-Hijaz,” pp. 185-97.

[56] Voice of America, Mar. 18, 2019.

[57] Ali Alfoneh and Michael Eisenstadt, “Iranian Casualties in Syria and the Strategic Logic of Intervention,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, D.C., Mar. 11, 2016; Alfoneh, “Four Decades in the Making: Shiite Afghan Fatemiyoun Division of the Revolutionary Guards,” Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, D.C., July 25, 2018.

[58] Reuters, Dec. 20, 2019.

[59] Ranstorp, Hizb’allah in Lebanon, pp. 119-28; Abbas William Samii, “A Stable Structure on Shifting Sands: Assessing the Hizbullah-Iran-Syria Relationship,” The Middle East Journal, Winter 2008, pp. 32-53.

[60] Kim Ghattas, Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Rivalry that Unravelled the Middle East (London: Headline Publishing Group, 2020), pp. 85-6.

[61] Smyth, “The Shiite Jihad in Syria and its Regional Effects"; Smyth, “Hizballah Cavalcade.”

[62] Oula A. Alrifai, “In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, D.C., Mar. 14, 2021; Carole A. O’Leary and Nicholas A. Heras, “Shiite Proselytizing in Northeastern Syria Will Destabilize a Post-Assad Syria,” Jamestown Foundation, Washington, D.C., Sept. 15, 2011.

[63] Tony Badran, “Arafat and the Ayatollahs,” Tablet (www.tabletmag.com), Jan. 17, 2019; Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam, p. 113-4.

[64] The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 24, 2009; Seth J. Frantzman, “Iran praises Palestinian PFLP for commemorating Soleimani on Quds Day,” The Jerusalem Post, May 10, 2020; The Times of Israel (Jerusalem), July 21, 2020; “Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade terrorist admits Hizbullah connection,” Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jerusalem, Dec. 12, 2005.

[65] Seth J. Frantzman, “Israel faced multi-front war during recent Gaza conflict,” The Jerusalem Post, June 2, 2021.

[66] Ali Khamenei, Twitter, @khamenei_ir, May 7, 2021.

[67] Al-Arabiya (Dubai), May 20, 2020.

[68] Ibid., Sept. 27, 2021.