The finances of American Muslim institutions tell us much about power, partnerships, and influence within the community. |

The first extensive look at the finances and structures of American Islamic nonprofit institutions reveals several key new understandings about both Islam and Islamism in the West. American Islam is a multi-billion dollar industry, whose wealth is disproportionally concentrated in the hands of Arab and South Asian Islamists tied to extremist networks around the world. With just a few notable exceptions, the institutions of those Muslim communities largely free from Islamist control appear relatively penniless.

In contrast to previous impressions that much of Western Islam is heavily subsidized by foreign radical regimes, most of American Islam’s revenue appears to be raised domestically. In fact, the flow of money is in the opposite direction to that previously supposed: American Islamic institutions send hundreds of millions of dollars overseas each year.

Our detailed look at American Islam’s finances – which we believe to be the first of its kind – also reveals enormous amounts spent on intra-Islamic grants and thousands of highly-paid employees, as well as extraordinarily high levels of expenditure and assets.

Previously, such estimates of American Islam’s institutions and their financial influence simply did not exist. Indeed, there is not even a consistent guess about how many Muslims live in the United States.

And yet, in the fight against Islamism and the effort to acquire new moderate Muslim allies and partners, truly understanding American Islam and its institutions is imperative. One of the most important means to understand ideological trends and the power of certain subgroups within a particular collection of communities is to gather and analyze its finances. Wealth and the movement of wealth tell us an enormous amount about power, partnerships, and influence.

As I have previously illustrated in some detail, the few existing studies of American Muslims and their institutions that are available rely on flawed methodology, rendered even more inaccurate by Islamist influences behind such surveys and the myriad of biases such dogma brings.

Drawn from a wide mix of open-source research, state corporation and federal nonprofit data, government databases, and a few existing studies, our own list of 5,600 American Muslim organizations appears to be the most extensive ever produced, although it is still not comprehensive.

However, keeping a completely accurate and current dataset is a Sisyphean task. Reasons for this are manifold. To list just a few: as with many nonprofit industries, there is a high turnover rate within American Islam’s institutions, with hundreds of groups falling defunct each year, and hundreds more established. In addition, an uncountable number of tiny mosques and prayer halls live on anonymously, hidden from external view, never seeking to incorporate legally or establish any sort of public presence beyond a friendly neighborhood service for a parochial network of families.

Nonetheless, we believe our list is a good enough sample us to produce some initial analysis with a very high degree of confidence.

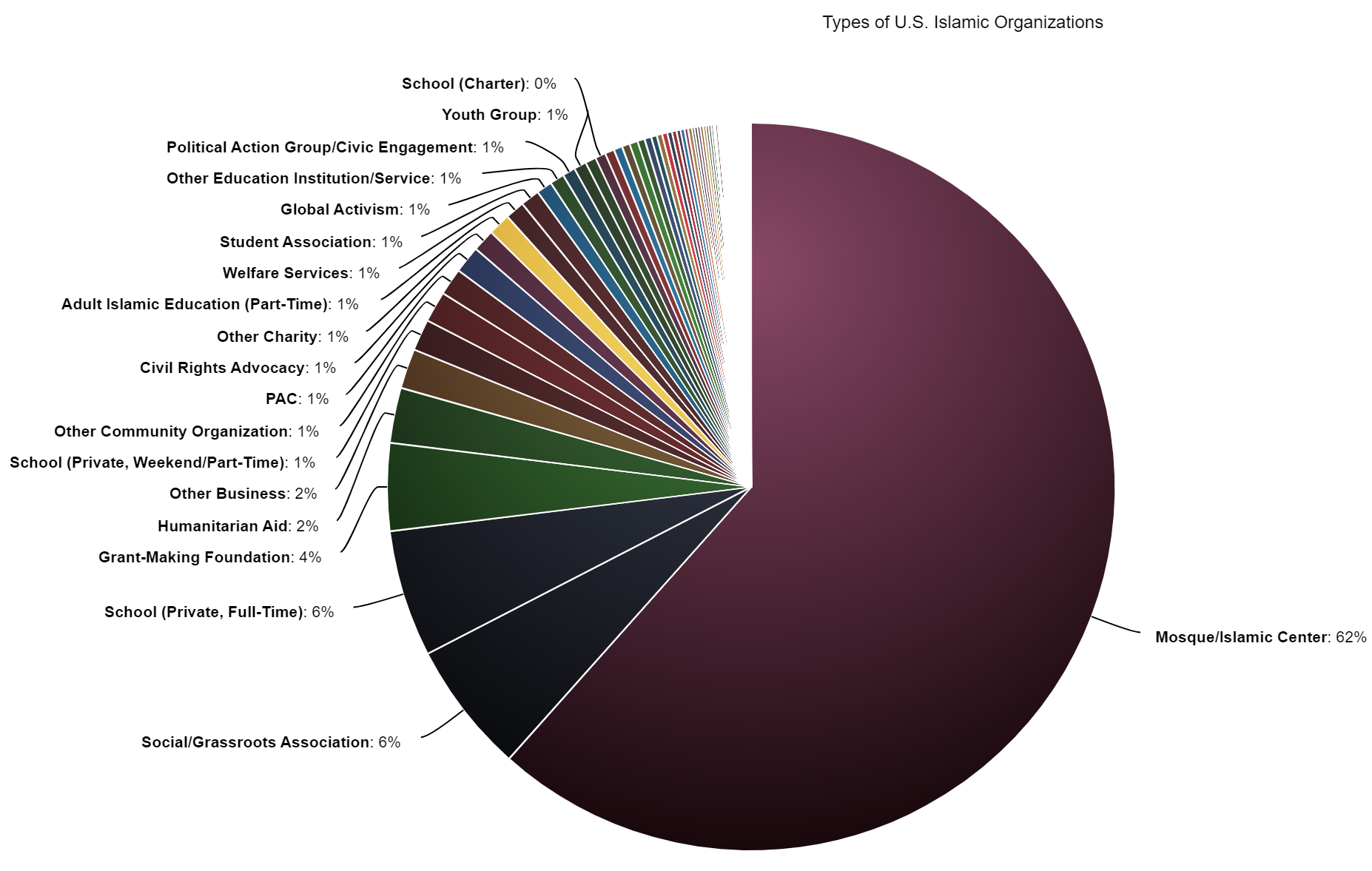

A breakdown of organizations by type is one such example. Almost two thirds of the known Islamic organizations in the United States are mosques or Islamic centers.

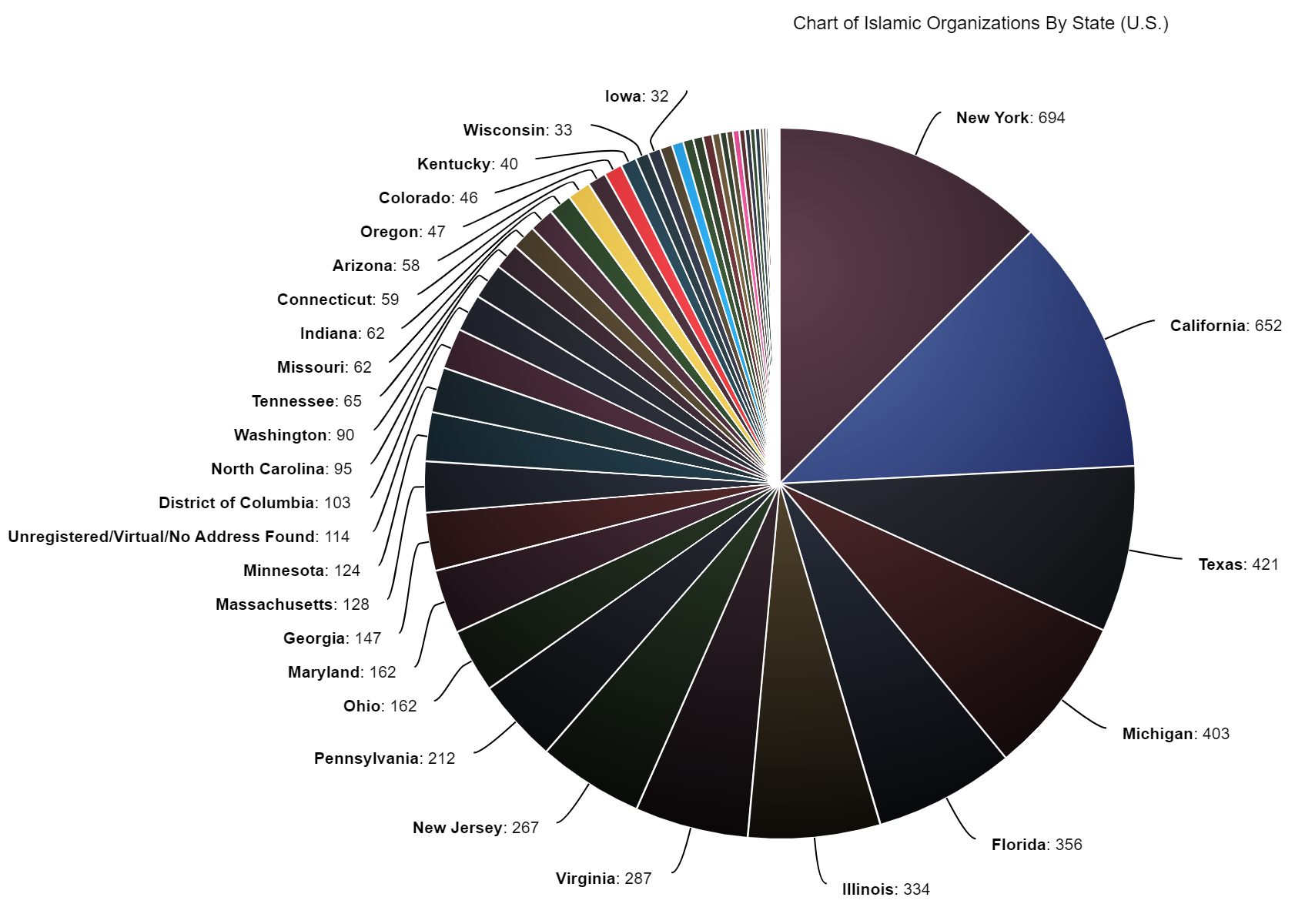

Similarly, the geographical spread of these 5,600 U.S. Islamic organizations can be accurately plotted. It is mostly as expected: significant concentrations in New York, California, Texas, Michigan, Florida, followed closely by various East Coast states.

Data Collection

The efforts to find out more than these basic details, however, encounters some obstacles. Among the almost 5,600 U.S. Islamic organizations we have identified, over 4,450 (some 80 percent) are, or have been, a registered 501(c). Just over 95% of these organizations are (c)(3) organizations, with just a few dozen (c)(4) groups and a scattering of more unusual 501(c) types.

In theory, it is through these 501(c) organizations, and the extensive reporting usually required of nonprofits, that we have the greatest hope of truly understanding the economics of American Muslim institutions.

In practice, American Muslim communities are diverse enough, filing requirements are foolish enough, existing datasets are skewed enough, and government datasets and reporting process are error-ridden and obfuscatory enough, that few samples with an acceptable margin of error can be generated.

Of the 5,600 organizations in our dataset, we have uncovered registered 501(c)s for 4,450 of them. But of those 4,450, only 1,570 have, at some point in the past few years, filed a searchable tax return. A whole host of additional reasons are to blame for this now drastically reduced final dataset.

First, there is the absurd exemption granted to places of worship that free them from the requirement to file tax returns while bestowing powerful tax benefits. It is hardly surprising, in line with their Christian and Jewish counterparts, that most mosques do not file tax returns. Second, a huge number of Islamic organizations report under $50,000 income each year, which also exempts them from having to file annual documents that reveal anything significantly more than their name and address. This means certain categories of Islamic organizations are far more likely to file tax returns than others.

Third, a considerable number of American Islamic organizations operate under the umbrella of other groups, and thus a single nonprofit registration can ultimately benefit a wide array of organizations and initiatives. For example, a single Islamic center may manage multiple mosques and schools; or a grant-making foundation may accept donations on behalf of an activist organization concerned with Palestine or Kashmir. Given such circumstances, tracking donations and their intended purposes becomes extremely difficult.

Finally, while electronic filing began in earnest ten years ago, it is only in the last few years that the majority of nonprofits have begun to make use of this option. As a consequence of this relatively slow digitization of nonprofit financial reporting, an overall view of the finances of American Islam is rendered yet more incomplete, given that ‘scraping’ financial details from many thousands of hard copy tax returns proves both difficult and extremely unreliable.

Thus, as a consequence of the flaws and circumstances of America’s 501(c) system, we can only get a reasonable look at a quarter of American Islam’s registered nonprofit institutions – some 1,570 groups. And, as explored above, that fraction itself is likely an overestimate, given the unknowable number of additional unincorporated bodies.

Still, this dataset is hardly insignificant. It is very much worth examining, on the condition that one always considers it a statistically skewed sample, given the four problems outlined above.

That said, even if our ability to understand American Islam is limited, the biases of the available data are such that we do get quite a bit of insight into American Islamism. Because of a desperate pursuit of control, along with deep ties to a myriad of national and international networks, Islamist-controlled organizations tend to be wealthier, and thus more likely to be required to file.

Furthermore, some Islamist institutions work towards what French journalists Christian Chesnot and Georges Malbrunot refer to as “micro-societies” – Islamic centers that do not just officer a prayer hall and other religious services, but housing, schools, welfare organizations or other services and amenities. The accompanying income and expenditure that accompanies such additional components tends to vacate the filing exemptions from which mosques would benefit, were they just humble houses of worship.

Thus, Islamist-controlled or influenced groups make up a substantial proportion of our remaining dataset and all its financial insights. And even without this glance into the economics of radicalism, the wealth of American Islam from this 25% alone is fascinatingly enormous.

American Islamic Wealth

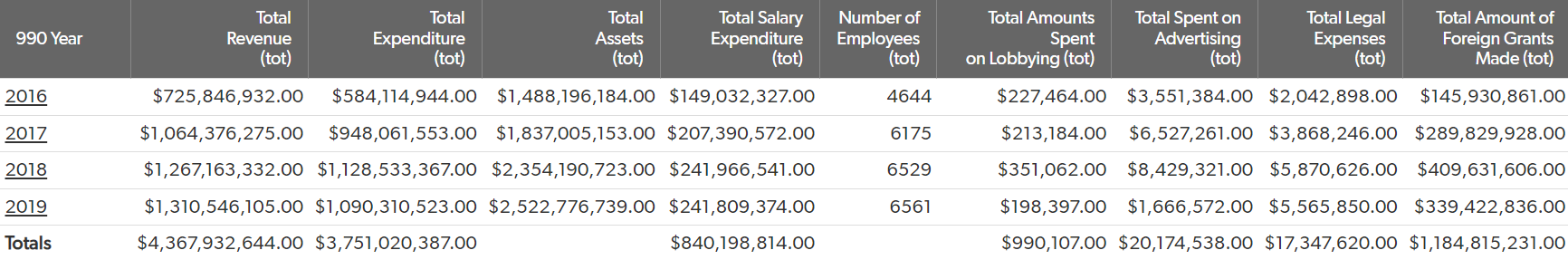

Taking just the most recent tax return for each of the 1,570 organizations that filed a searchable, electronic tax return, we can see that a quarter of Muslim American institutions declared, astonishingly, a combined total of over $3.1 billion of total assets and $1.6 billion of total revenue.

Over the past three years, the average combined annual revenue for this 25% of American Islamic institutions has been $1.2 billion.

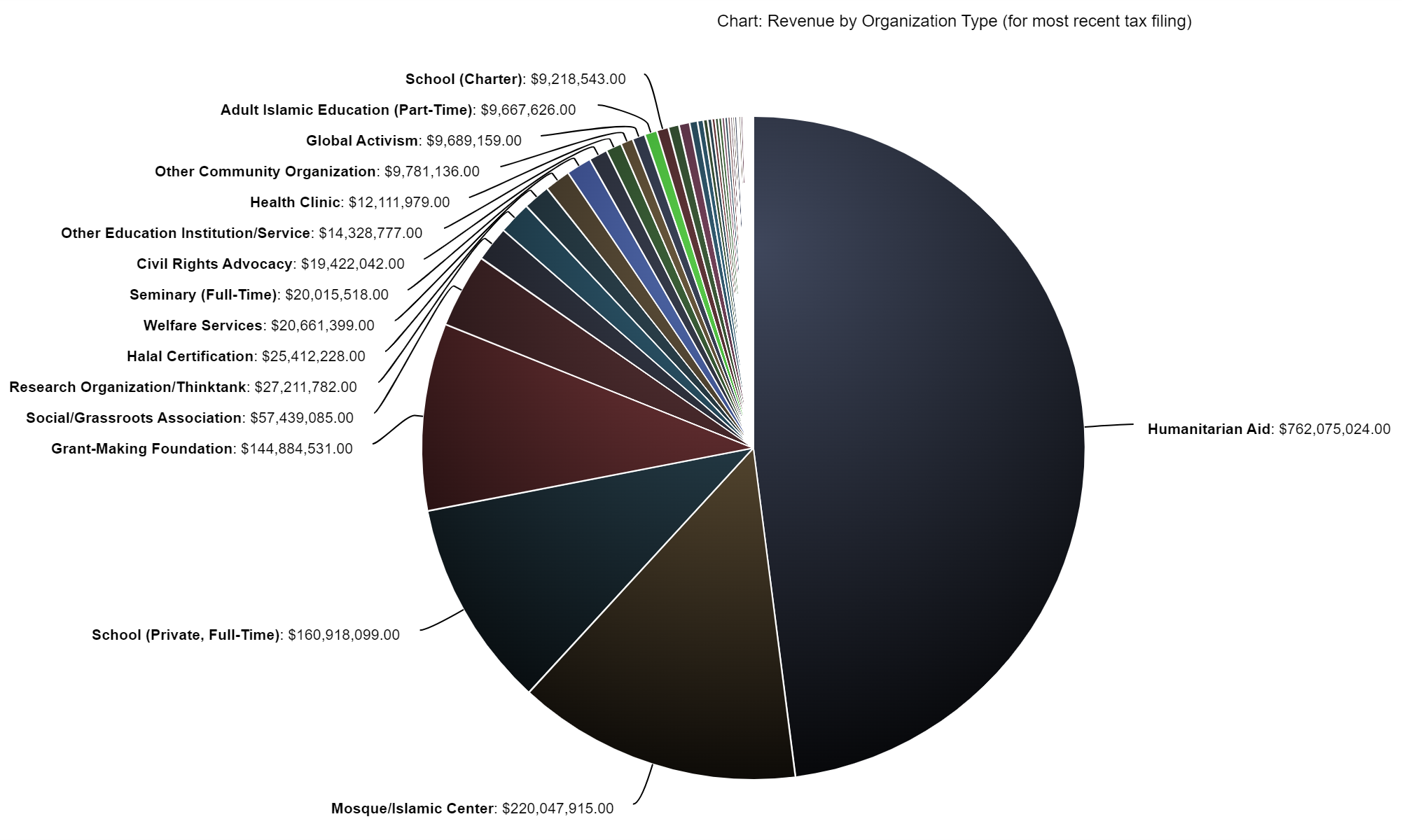

Almost half of this revenue has been raised by Islamic humanitarian aid charities.

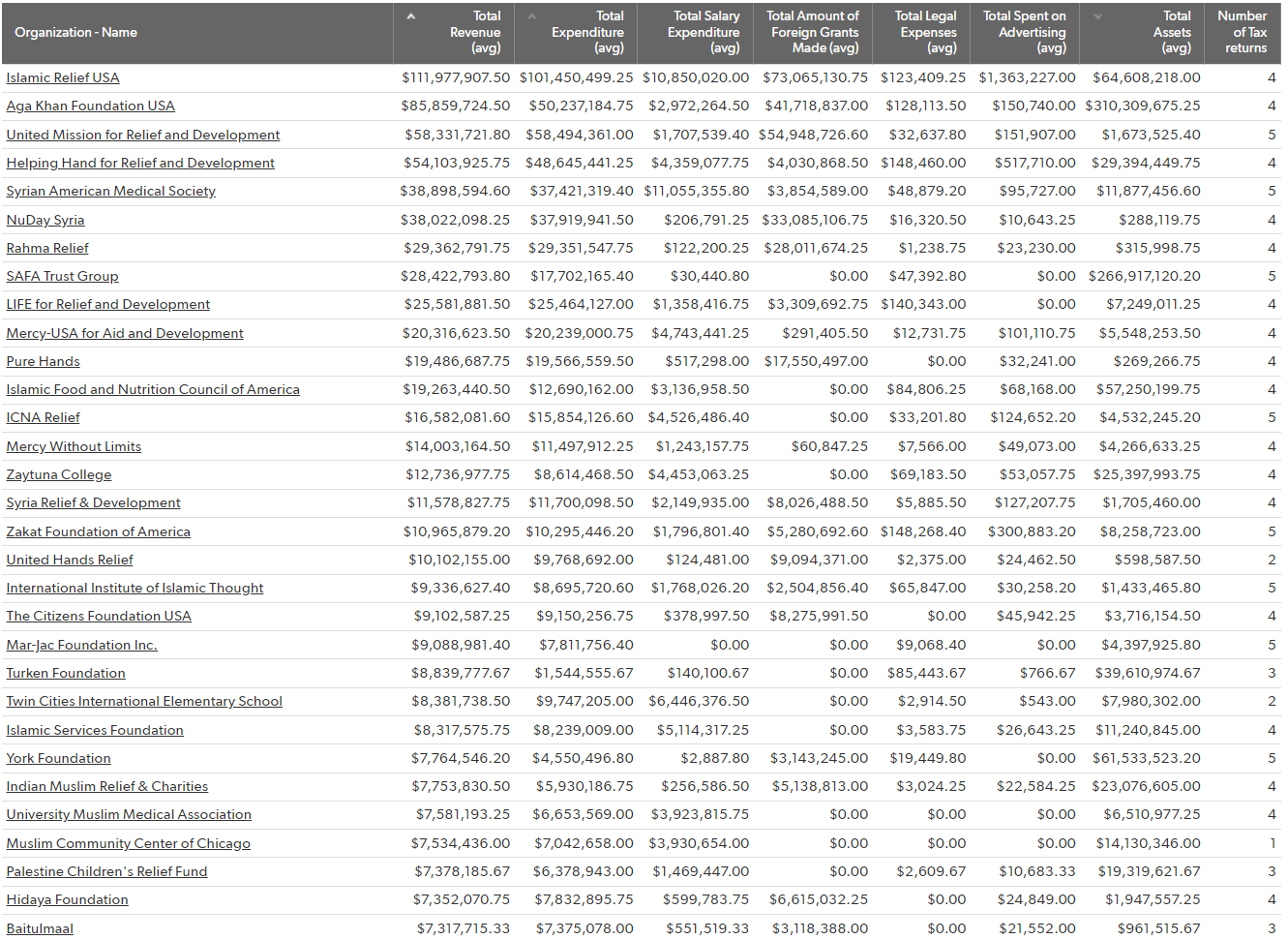

It is not particularly surprising that American Islam’s most wealthy organizations are predominantly aid charities. This is presumably not too dissimilar for other religious communities. It remains alarming, however, that a clear majority of these financial behemoths in our sample are Islamist-controlled.

Among the richest charities is Islamic Relief USA, a prominent anti-Jewish branch of the terror-tied international franchise Islamic Relief. Widely denounced as a Islamist-controlled or terror-linked by European and Islamic governments, Islamic Relief and its officials have a long history of close ties to Hamas and other designated terrorist groups. In 2020, the State Department published a statement condemning Islamic Relief’s glorification of terror and the extremism of the charity’s senior officials, and noted the “well-documented record of anti-Semitic attitudes and remarks made by the senior leadership of Islamic Relief Worldwide.” The U.S. branch raises over an average of $110 million each year.

Front organizations for the South Asian Islamist movement, Jamaat-e-Islami, also feature at the very top of America’s most wealthy Islamic groups. ICNA Relief and its sister charity, Helping Hand for Relief and Development, collaborate with dangerous Pakistani Islamist groups, once including the designated terrorist organization Lashkar-e-Taiba. These groups and the rest of the U.S. Jamaat-e-Islami network annually declare combined average assets of almost $60 million and average combined annual revenue of $80 million.

Turkish regime-linked organizations, such as the “Turkish-backed” Zakat Foundation of America and the Turken Foundation, which was founded and managed by members of regime leader President Erdoğan’s own family, also feature at the top of the list. Together, Turkish regime-linked American Islamic nonprofits annually report an average of over $163 million of combined assets.

Other groups listed in this top 30 include charities with demonstrable links to proxies for the terror group Hamas and other extremist entities. These charities include entities such as LIFE for Relief and Development, Baitulmaal, United Hands Relief and Syria Relief & Development.

Meanwhile, others in the top list include organizations such as the SAFA Trust Group, Mar-Jac Foundation, York Foundation, and the International Institute of Islamic Thought, all of which are part of a Virginia-based operation known as the SAAR network, a collection of Islamist groups investigated heavily by federal agents in the 2000s for terror finance ties. Today, the registered 501(c)s for the entire of the SAAR network’s nonprofit organizations report an astonishing combined total of over $400 million of assets.

There are a few moderate organizations among the top recipients. The Ismaili-run Aga Khan Foundation, for example, is a particularly prominent example. But one conclusion comes through clearly: the Islamists control most of the money.

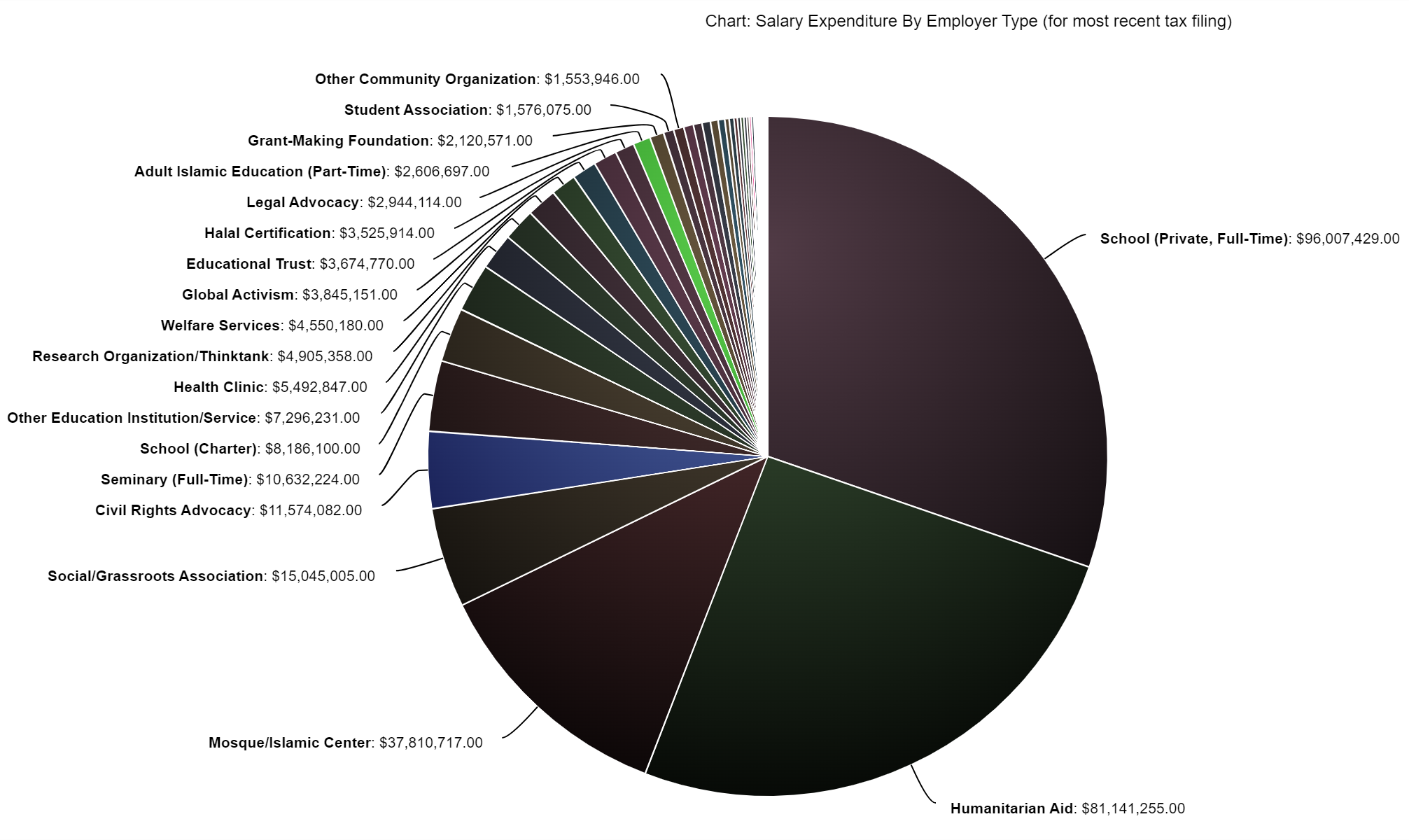

This enormous nonprofit industry is also an important employer within American Islam. Taking the most recent tax return, our sample of American Islam’s nonprofit organizations report spending an annual total of almost $320 million on salaries between, employing almost around 7,000 people.

Some of these nonprofits do not appear particularly selfless endeavors. Several dozen nonprofit organizations report average salaries of well over $100,000 per employee. At the most extreme end, Islamist-linked organizations such as Syria Relief & Development once reported spending over $7.6 million on annual salaries for just 4 declared employees – almost $2 million per staff member. Various other Islamist-linked aid charities, such as Mercy-USA for Aid and Development, report similarly, extortionately large average salaries. Repeated yearly errors or oversights in their filed tax returns could perhaps explain some of these discrepancies.

Conversely, many dozens of Islamic organizations – some with assets of tens of millions of dollars – report large numbers of employees but nothing or negligible amounts spent on salaries. Such ratios suggest third parties subsidizing or covering employee costs, indicating Muslim American nonprofits are an even more lucrative employer than IRS data would imply.

Some instances are explicable. The 2014 tax return for the Diyanet Islamic Center in Maryland, for instance, reports 76 employees but no salary expenditure at all. The Diyanet Center is an office of the Turkish regime’s Directorate of Religious Affairs. The salaries of this enormous institution’s officials and staff, then, appears to have been almost certainly paid for directly by the regime. (Incidentally, the Diyanet Center today reports to be the wealthiest mosque in the United States, declaring almost $94 million of total assets in its most recent tax return).

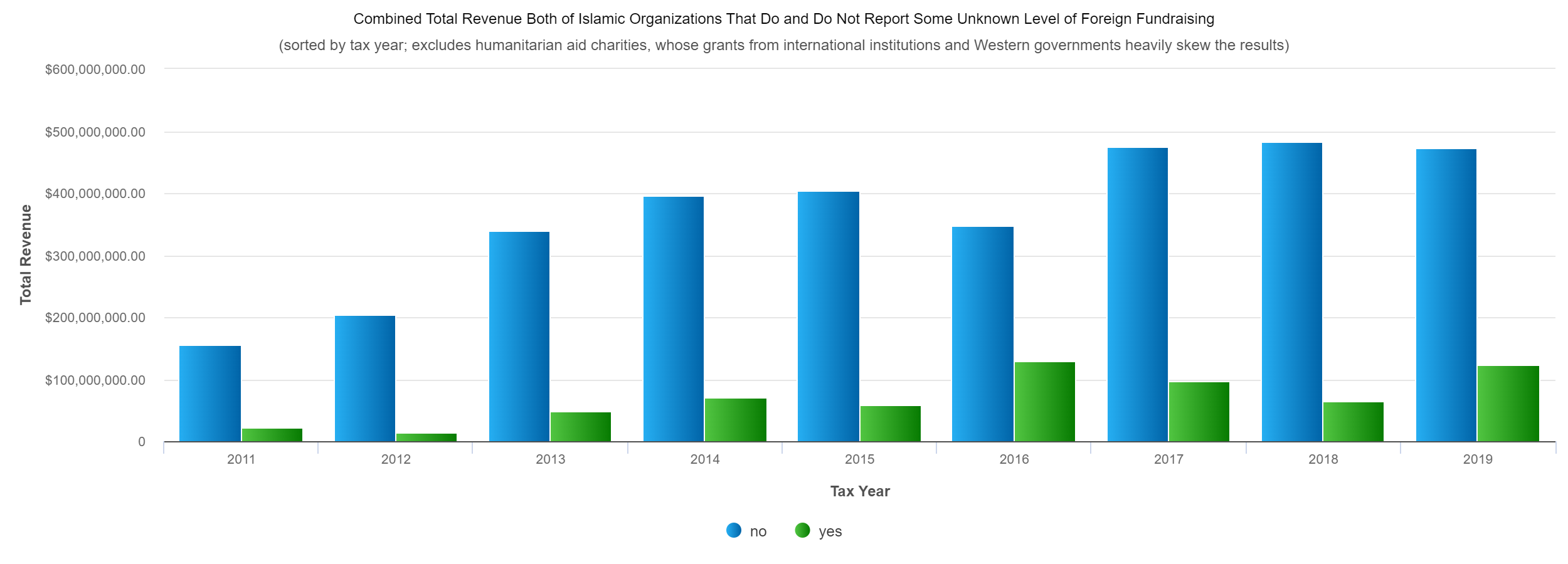

Indeed, international finance matters affect a great deal of the American Islamic nonprofit industry, but not in the direction many would presume. An astonishing proportion of the money raised by Islamic organizations in the United States is subsequently sent overseas. Humanitarian aid charities, whether Islamist controlled or not, play a large part in this. Of the $8 billion reported by 1,570 organizations in their electronically-filed tax returns over the past decade, over $2.1 billion of this sum was sent abroad.

Several other interesting datapoints emerge. Almost a third of the 1,570 organizations report foreign fundraising over $10,000 or foreign investment over $100,000; and over a third of the organizations report making grants to foreign individuals or organizations.

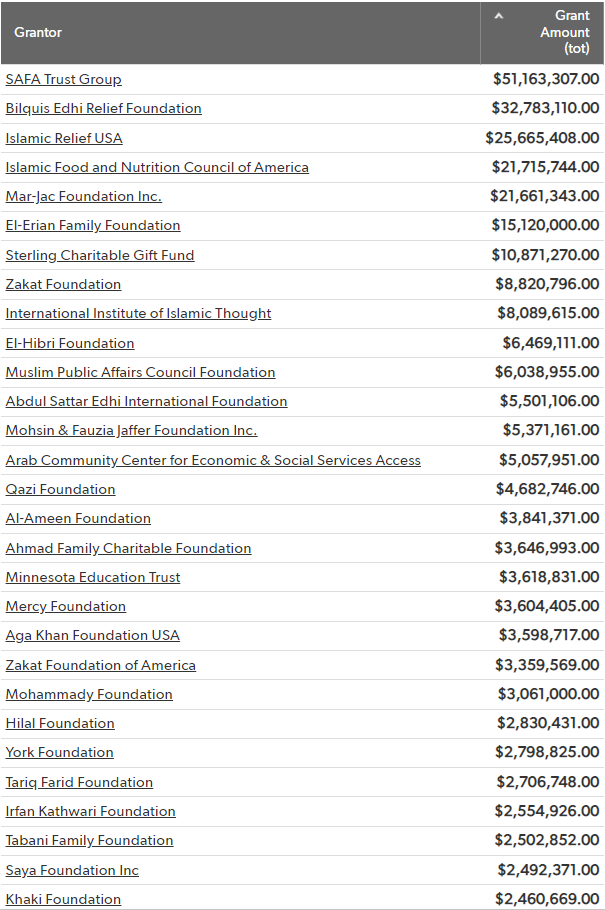

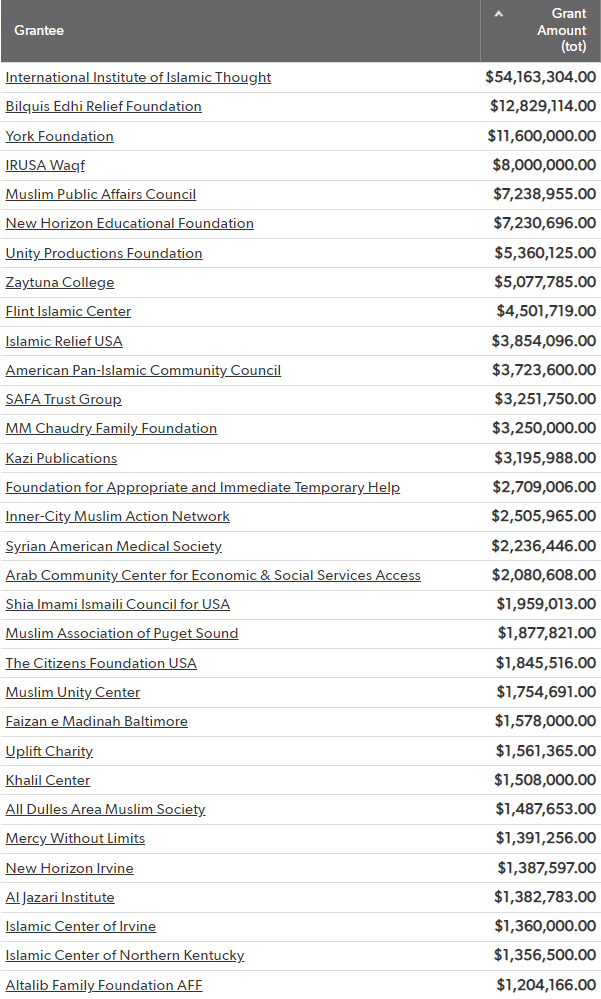

The details of grants issued by the Islamic 501(c) industry are also worth examining. While tax returns do not generally record a 501(c)'s donors, they do list its grantees. For all the available electronically-filed data, American Islamic 501(c)s report providing a total of almost $410 million, in the form of 15,700 grants, issued by just 370 organizations, to almost 5,000 organizations around the world. It appears 70 percent of the total amounts end up with organizations that are Muslim-run.

The data reveals that attentions may not been always focused on the right networks over the past twenty years. It is particularly interesting, for example, that institutions representing the U.S. arm of the Pakistani-based Barelvi movement, Dawat-e-Islami, feature both among the top donors and recipients. Almost entirely ignored by Western law enforcement, counter-extremism analysts and media, Dawat-e-Islami operates over a dozen institutions in America and, internationally, it has a history of deeply concerning ties to extremism and terror.

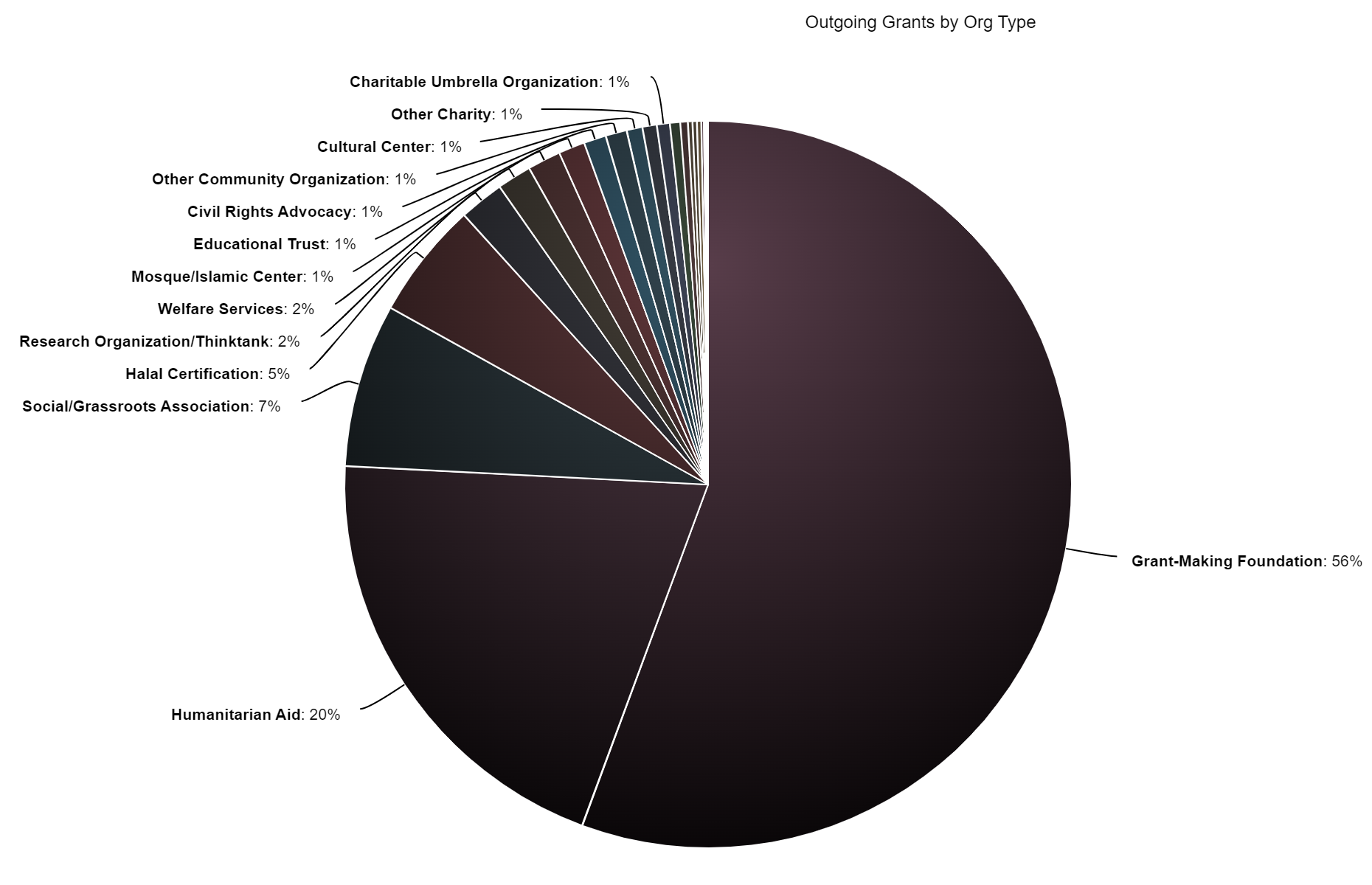

The Islamic grant-making industry is enormous. And grant-making foundations, while just making up 4% of all American Islamic organizations, are responsible for over 60% of the total sum of grants handed out.

The level of Islamist control over this important grant-making subset of American Islam appears high. In fact, as I have previously exposed in some detail, in Michigan, a wealthy and influential collection of scores of grant-making foundations, linked to just one accountancy firm, moves many tens of millions of dollars to radical organizations both in the United States and overseas.

Meanwhile, over the past ten years, based on available electronic filings, American Islamic organizations report receiving over $280 million in grants from other U.S. Islamic 501(c) organizations, and over $100 million in grants and payments from the federal government (a considerable amount of which, surprisingly, was provided under the Trump administration, and the majority of which ended up in the hands of organizations with extremist links).

What Have We Learned?

As stated at the outset, this dataset of ours only represents an unrepresentative quarter of American Muslim institutions. It affords us little clarity about the financial activities of the entire of American Islam, given the biases that skew our sample so dramatically. We can reasonably assume, however, that this is the wealthiest quarter of American Islam. And thus, a few interesting conclusions can be generated.

To start with, American Islam is - as should be apparent by now - extraordinary wealthy, funded with billions of dollars. But this wealth is disproportionately concentrated in the hands of grant-making foundations and charities connected to specific, unrepresentative Islamist movements, which, in turn, distribute monies further to a wide variety of Islamist recipients. Organizations tied to international Islamist networks and foreign theocratic regimes feature at the very top of the list of American Islam’s most affluent groups.

There is also a curious ethnic spread as well. While Arab and South Asian charities and foundations – many with ties to Islamist networks - appear to control most of American Muslim wealth, institutions belonging to African, Central Asian, far-Eastern and Black American communities (in which Islamist influence is much more rarely found) appear mostly penniless. Arab and South Asian Islamists are, it seems, the “one percent.”

Second, while enormous amounts of monies have been distributed through intra-Islamic grants (considerably to the benefit of Islamist groups) such financial transactions remain a relatively small proportion of American Muslim organizations’ billions of dollars of annual revenue. An actual breakdown of income sources for most American Muslim institutions remains elusive. Given the size the sums, it seems unlikely, however, that the remaining amounts are provided simply through zakat contributions or from occasional internet fundraising drives.

Far more American Muslim money is sent overseas then is raised overseas.

Third, despite the obscurity of the income sources, it seems a reasonable inference that far more American Muslim money is sent overseas then is raised overseas. Islamist organizations play a large part in this statistic. But more importantly, it suggests that today, American Islam, and thus by extension, American Islamism, appears to be largely self-financed, probably funded by a fast-growing and increasingly affluent Muslim middle-class along with a growing number of extremely rich businessmen and their grant-making foundations. Of course, this conclusion does assume that Islamist organizations are being honest in their tax filings about overseas financial activities. This is not such a far-fetched assumption, given the emphasis so many Islamist groups place on operating lawfully.

This growing self-reliance would also explain the curious lack of public source evidence that much financial support from Islamist governments – such as Qatar and Turkey – is directly provided to American Islamist organizations. While these regimes happily pour some money into their own institutions and proxies in the West, as well as lobbyists and media, it would seem foreign Islamist regimes are no longer as important as donors to American Islamist institutions as they once were, a far cry from the days when Saudi Wahhabi monies were widely and persistently solicited.

What Next?

This brief look into the economics of American Islam and its Islamist components was made possible only by the slow digitization of tax filing records. Given new electronic filing requirements imposed last year by the IRS, the level of insight we can glean will only improve over the next few years. But the continued exemptions on offer that allow too many religious organizations to avoid transparency over their activities and finances, while benefiting from tax exemptions, federal grants and other public benefits, is a dangerous state of affairs, from which radical organizations have benefited considerably.

Greater transparency and less government foolishness remains, as always, a key line of defense against the theocratic and other totalitarian menaces that threaten Western society.

Now, the obvious next step for counter-extremism analysts is a complete ideological mapping of American Islam. Understanding the influence of different Islamic movements and sects, and combining that analysis with increasingly-extensive financial breakdowns, will provide even greater insight into the activities and finances of American Islam.

Most importantly, ideological and financial mapping will serve as a powerful counter-extremism tool. Truly gauging the makeup of American Islam will allow us not just to identify the extremists and their wealth, but also to uncover new moderate and reformist allies. It is only by truly understanding Western Islam that we can fight Western Islamism.

Sam Westrop is director of the Middle East Forum’s Islamist Watch project.