|

|

Robert Rabil, professor of political science at Florida Atlantic University, spoke to a June 5th Middle East Forum Webinar (video) about the conditions that led to Lebanon becoming a failed state. The following is a summary of Rabil’s comments:

Modern Lebanon emerged as a state in 1920 under the French Mandate. The latter instituted a “confessional system” based on the distribution of power along religious lines and modeled after the system used under the Ottoman Empire. Christians held a slim plurality. After 1943, Lebanon became independent, and the Christians and Muslims formed a “national compact.” It was a system that relied on the Christians’ efforts to “Lebanonize” the Muslims, and the Muslims’ efforts to “Arabize” the Christians; neither was successful.

Two developments followed: (1) Lebanon transitioned from a system of feudalism “based on tax farming” to one based on political sectarianism, whereby politicians created a weak and corrupt patronage system that favored sects instead of national identity. Lebanon changed from the “Paris of the Middle East” into “a fodder for spoils"; and (2) the disruption of the confessional system in 1958, caused by a split between the Christians who supported the Eisenhower Doctrine (i.e. they maintained a pro-Western political orientation) and the “strident nationalism” of Nasserism among the Muslims, spawned a civil war from 1975 to 1990.

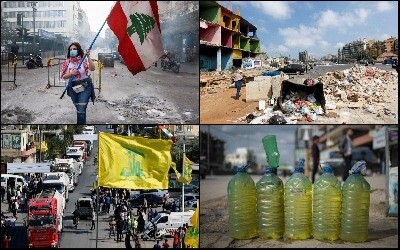

The resulting power vacuum in Lebanon’s broken system was filled by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). This non-state actor, which emerged as a “strong power broker” in Lebanon under its “kingmaker” Yasser Arafat until the Israelis invaded in 1982 and evicted them, became the “catalyst” for the civil war, which in turn paved the way for the rise of Hezbollah. Supported by Syria, Hezbollah filled the power gap created by the Lebanese civil war. Syria then occupied Lebanon from 1990 to 2005, during which time Hezbollah became “a state within a state.”

Hezbollah’s military might, reinforced by its support of the social infrastructure, built a following among the Shia who had been given short shrift by the sectarian political elite. Hezbollah remained dominant following the assassination of Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in 2005. A cross-sectarian uprising of Lebanese Christians and Muslims came together following the assassination and took to the streets, ousting Syria. Hezbollah reached a “fortune pact” with the remaining political elites that had “robbed the state” and went so far as to steal depositors’ monies in the country’s banks after the October Revolution in 2019. The World Bank has said regarding the country’s current situation that Lebanon was “facing the worst crisis since the mid-nineteenth century.”

As Hezbollah’s power grew, the terror group dismantled militias formed during the Lebanese civil war and emerged as a “huge actor” not only in the Syrian civil war, but also in Iraq, and then in Yemen. Hezbollah’s power grab embroiled the Lebanese people in its schemes, hijacking the people’s consent over the issue of war or peace. Today, Hezbollah, with weaponry from Iran and support from Syria, does Iran’s bidding under the banner of “the Axis of Resistance.”

The influx of Syrian refugees fleeing Syria’s 2011 civil war triggered another crisis in Lebanon. Initially, the Lebanese welcomed the refugees when low in number, but the trickle became a deluge in 2015 as Syria’s civil war intensified. According to Lebanese statistics, the country of five million now has two million Syrian refugees, “the largest number of Syria[ns] per capita refugee[s] in the world.” Lebanon’s history of socio-economic and political crises, along with the ravages inflicted by a corrupt political elite, has left it a failed state.

The Lebanese currency has lost 95 percent of its value, and a crumbling health system, sporadic electricity, and a paucity of potable water now has tensions spiking between the Lebanese and the Syrian refugees as they compete for scarce resources. UN aid is unable to fill the gap, as 80 percent of the Lebanese people are at or below the poverty level, and 50 percent face food insecurity. In order to receive more aid from the UN, the Syrians have taken on multiple wives and increased their number of children. Consequently, Syrian births in Lebanon now exceed births to Lebanese in Lebanon.

Although the Lebanese army is the only functioning institution in the country, it is under strain due to the plummeting Lebanese lira and its devaluation of salaries. The Christian forces are debating remedies to address Lebanon’s ills, including a system of federalism. However, it has little chance of adoption because it relies upon sharing power, which the Sunni and Shia do not support. “The Christian community is fragmented, the Sunni community is leaderless, the Druze community acts from the position [of] political survival, and the Shia community has the gun.”

The Christian community is fragmented, the Sunni community is leaderless, the Druze community acts from the position [of] political survival, and the Shia community has the gun.

A possible solution would be for the new generation of Lebanese youth to form a “new pact” based on removing sectarian leaders and their patronage system’s monopoly on power and coalescing to create one national identity based on full democracy and transparency. The “despondency” rife among the population is causing mass migration. “The dynamics of Lebanon are very complicated, very complicated, and it’s very difficult for any party to go in and bring that communal peace if the Lebanese – they don’t have this communal peace themselves.” With the encouragement of the U.S. and the European Union, the long-term project towards restoring Lebanon’s civil society can start with reducing its reliance on Hezbollah’s social infrastructure.

Currently, Rabil is concerned that the Saudi-Iran agreement, and the growing rapprochement between Russia and Iran because of the former’s war in Ukraine, have emboldened Hezbollah. The strategic cooperation between Russia and Iran has transitioned into a “strategic alliance” that may influence Russia’s adherence to its former “red lines.” Hezbollah aims to receive more sophisticated weaponry from Russia, and, under the circumstances, Russia may not restrict weapons smuggling from Syria to Hezbollah. Such an outcome would affect Israel’s security and, in turn, Lebanon’s. For centuries, Lebanon was able to survive invasions “from the Mamluk to the Fatamid,” but the next generation’s ability to form this new pact would be a “litmus test” of whether Lebanon can be saved.