No sooner had the Palestinian Arabs fled their homes during the 1948-49 war than they were taken under the protective wing of the international community and protected like no other group in similar circumstances. This special treatment ranged from their very recognition as refugees despite the failure of many to satisfy the basic criteria for such status, to the unprecedented creation of a relief agency committed exclusively for their welfare: the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, or UNRWA.

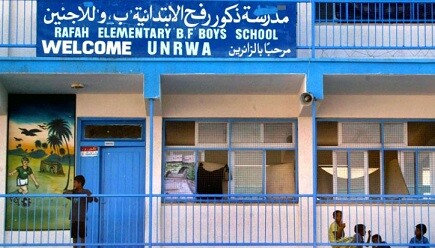

Yet rather than help resolve the Palestinian refugee problem, this unparalleled indulgence has only served to confirm its permanency. And no factor has contributed more to this perpetuation than UNRWA, which, instead of ending direct relief and transferring responsibility for the refugees to the host Arab states within months, as stipulated by its mandate, has kept them on the U.N.'s dole for decades under false humanitarian pretense.

Singled out for Privilege

World War II created an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. In Europe alone, more than 16 million refugees and displaced persons languished in search of a solution to their plight. This included some 13 million Germans expelled from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and other East European countries; nearly 2.5 million Poles, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Russians, and Lithuanians driven from their homelands to their newly demarcated states; some 250,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors herded in overcrowded camps (mainly) in the country that had just slaughtered six million of their brothers; and over 400,000 Finns driven from Soviet-occupied Karelia for the second time in half-a-decade.[1]

Not only has UNRWA not helped to resolve the Palestinian refugee problem, it has amplified the problem. UNRWA was initially envisaged as a short-lived agency, but its mandate was perpetuated by declaring Palestinian “refugee” status hereditary, allowing its application to descendants of the original refugees.

These massive refugee problems were handled by the International Refugee Organization (IRO), established by the U.N. General Assembly in December 1946 and succeeded in January 1951 by the High Commissioner’s Office for Refugees (UNHCR), which rapidly expanded its initial Eurocentric outlook to include refugees and displaced persons from all over the world. There was only one exception to this pattern: the Arab escapees of the 1948-49 war who received their own relief agency, the United Nations Relief for Palestine Refugees (UNRPR), set up in November 1948 and succeeded on May 1, 1950 by UNRWA. And while UNHCR was created on a shoestring annual budget of $300,000,[2] UNRWA was established on the assumption that “the equivalent of approximately $33,700,000 will be required for direct relief and works programmes for the period 1 January to 31 December 1950.”[3] In other words, the Palestinian refugees received 110 times the money allocated to the treatment of all other refugees throughout the world.

Sixty-eight years later, UNHCR comprises nearly 11,000 personnel handling 17.2 million refugees (or 1,568 refugees per worker) and 65.6 million forcibly displaced persons compared to UNRWA’s 30,000-plus employees handling some 5.3 million “refugees” (or 176 refugees per worker). That is: Palestinian “refugees” receive ten times the human resources as their less fortunate counterparts anywhere in the world, and 34 times the humanitarian support extended to displaced persons worldwide.[4]

The word “refugees” has been put in quotes with regard to the Palestinians currently cared for by UNRWA for the simple reason that they do not correspond to the conventional refugee concept, which views this phenomenon as a temporary plight that needs to be rectified swiftly. As early as 1929, the League of Nations decided that its International Office for Refugees would shut down within a decade at the most. Its U.N. successor, the International Refugee Organization, was similarly created as a temporary organ due to cease activities by the end of 1950 while the High Commissioner’s Office for Refugees was initially conceived as a three-to-five-years-long agency.[5]

Likewise, the U.N.'s Relief for Palestine Refugees was set up on the assumption “that the problem would be resolved in a matter of months,”[6] and even UNRWA was initially envisaged as a short-lived agency though it quickly had its mandate perpetuated by uniquely making the Palestinian “refugee” status hereditary so as to allow its indefinite application to descendants of the original refugees.[7]

What makes this distinct self-perpetuating leniency all the more extraordinary is that even the original designation of the Palestinians as refugees ran counter to both the standard definition of this status and the international treatment of similar, if not worse, contemporary humanitarian predicaments.

Real Refugees?

Misconstruing failed aggressors for victims. The notion of refugees and displaced persons has been invariably equated with unprovoked victimhood: being on the receiving end of aggression. Members of aggressing parties, including innocent civilians victimized as a result of their governments’ aggression, have been viewed as culprits, undeserving of humanitarian international support.

Thus, for example, not only did the IRO constitution deny refugee status to the millions of “persons of ethnic German origins” driven from their homes in the wake of the war—thereby forcing West (and East) Germany to resettle them in their territories at their expense—but it also singled out persons who “have voluntarily assisted the enemy forces since the outbreak of the second world war in their operations against the United Nations.” It moreover stipulated that Germany and Japan should pay, “to the extent practicable,” for repatriating the millions of people displaced as a result of their wartime aggression.[8] Likewise, Finland not only had to absorb the 400,000-plus Karelian refugees with no international support but was forced to pay massive reparations to Moscow for having assisted the German attack on the Soviet Union.

Child refugees at Wilhelmshaven, Germany. After World War II, Europe saw more than 16 million refugees and displaced persons. UNRWA received 110 times the funds for the 600,000 Palestinian refugees than the amount allocated for all other refugees throughout the world. The Germans as aggressors were not recognized as refugees, but the Palestinians were.

In contrast, the Palestinians and the Arab states have never been penalized for their “war of extermination and momentous massacre,” to use the words of Arab League secretary-general Abdul Rahman Azzam,[9] against the nascent state of Israel. Quite the reverse, in fact. Despite U.N. secretary-general Trygve Lie’s admonition that “the United Nations could not permit that aggression to succeed and at the same time survive as an influential force for peaceful settlement, collective security, and meaningful international law,”[10] the Palestinians and the Arab states were generously rewarded for that very aggression. The former have become the most privileged refugee group ever; the latter have been generously remunerated for hosting the displaced persons whose dispersal they caused in the first place.

This unprovoked war of aggression should have ipso facto precluded the Palestinians from refugee status, should have obliged them to compensate their Jewish and Israeli victims, and should have made their rehabilitation incumbent upon their leaders and the Arab regimes as with post-World War II Germany and collaborating parties. However, it did not. In addition, their designation as refugees also failed to satisfy the internationally accepted definition of this status in several other key respects.

“Internal refugees”? The IRO constitution defined refugee as “a person who has left, or who is outside of, his country of nationality or of former habitual residence,”[11] and this definition was reaffirmed by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which applied the term to any person who “is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or … unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events is unable or ... is unwilling to return to it.”[12] This definition has been expanded by the UNHCR without changing its general gist to include “persons who are outside their country of nationality or habitual residence and unable to return there owing to serious and indiscriminate threats to life, physical integrity or freedom resulting from generalized violence or events seriously disturbing public order."[13]

The equation of refugeedom with being outside the national homeland was neither accidental nor a semantic sophistry. Apart from the immense dislocation occasioned by World War II, the immediate postwar years saw a number of massive population dispersals, notably the 13 million Hindus and Muslims displaced during the 1947 partition of the Indian Subcontinent into the new states of India and Pakistan; the millions dispersed during the Chinese civil strife, and the 700,000 displaced during the Greek civil war.[14] Overwhelmed by the post-World War II European refugee crisis and daunted by the magnitude of the problem elsewhere, the newly established United Nations sought to shun responsibility for these crises as evidenced by the IRO constitution and the deliberations leading to its replacement by the UNHCR and the 1951 refugee convention. Insisting that the protection of refugees “could only gain substance if it were given by all the Members of the United Nations,” the U.S. representative (and former First Lady) Eleanor Roosevelt emphasized the impracticality of the idea. Only eighteen states had become members of the IRO while most other governments refrained from doing so mainly for financial reasons, she argued.

It would, therefore, be better to adhere to the IRO’s definition of refugees that focused on protecting those outside their national homeland than to seek the unattainable goal of providing material assistance to “all categories of refugees existing in any part of the world.”[15] As this line of thinking prevailed, the millions of Indian, Pakistani, Chinese, and Greek “internal refugees” were not recognized as refugees by the 1951 convention.

There was, however, once again, one notable exception: the Palestinians. While 480,000 of the 600,000 Palestinian Arabs who fled their homes during the 1948-49 war—or 80 percent—remained in what used to be the country of their nationality at the outbreak of hostilities, namely mandatory Palestine,[16] they were, nevertheless, recognized as refugees. And by way of legitimizing this aberration, the 1951 convention specifically excluded the Palestinians from the need to comply with its definition as a result of them benefitting “from the protection or assistance of a United Nations agency other than UNHCR.”[17] This allowed UNRWA to adopt the highly inclusive definition of a refugee as “a needy person, who, as a result of the war in Palestine, has lost his home and his means of livelihood,” aware of the countless borderline cases resulting from the continued presence of the “refugees” in their country of nationality:

In some circumstances, a family may have lost part or all of its land from which its living was secured, but it may still have a house to live in. Others may have lived on one side of the boundary but worked in what is now Israel most of the year. Others, such as Bedouins, normally moved from one area of the country to another, and some escaped with part or all of their goods but could not return to the area where they formerly resided the greater part of the time.[18]

American Friends Service Committee members hand out blankets to Palestinian refugees, Gaza, 1948. A British diplomat was told by refugees that “they have no quarrel with the Jews… and are perfectly ready to go back and live with them again.” They clearly had no “well-founded fear of being persecuted.”

Yet these displaced persons remained in their country of nationality and could have readily rebuilt their lives there as ordinary citizens rather than refugees, either by being allowed to proclaim their own independent state in the West Bank and Gaza, as stipulated by the partition resolution of November 1947, or as citizens of the respective occupying states.

Indeed, the 280,000 escapees in the West Bank, alongside the 88,000 who had fled to Transjordan (east of the Jordan River)—i.e., a total of 368,000, more than 60 percent of those who had fled their homes during the war[20]—became Jordanian citizens even before the area’s official annexation to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

This, on its own, should have disqualified them for refugee status as both the IRO constitution and the 1951 convention unequivocally deny this status and its attendant benefits to any refugee who “has acquired a new nationality, and enjoys the protection of the country of his new nationality.”[21] In line with this ruling, in 1952-53, the High Commissioner for Refugees declined Ankara’s request to grant refugee status to the 154,000 persons of Turkish origin who had been expelled from Bulgaria on the grounds that they ceased to be refugees upon receiving Turkish citizenship.[22] Yet this principle has never been applied to the Palestinians who have been granted Jordanian citizenship or their descendants—amounting to some 3 million “refugees” in today’s terms.

Even less deserving of refugee status are the Palestinians who moved from the West Bank of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to its eastern bank during the June 1967 war. Not only did they remain in the country of their nationality under the rule of their own government, but as members of the aggressing party, they did not meet the basic requirement for refugee status: victimhood.On June 5, at the outbreak of hostilities on the Egyptian front, Israel passed several secret messages to Jordan’s King Hussein, pleading with him to stay out of the fighting and pledging that in such an eventuality, no harm would be visited upon his kingdom.[23] Had the king heeded these pleas and refrained from attacking Israel, there would have been no war, and the West Bank would have remained under his control.

Justified flight? Last but not least, the 1951 convention linked people’s flight from their national homeland, which qualified them for refugee status, to “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”[24] Yet no such fear should have existed in the Palestinian case—not in 1967, when it became evident within days that West Bankers faced no imminent threat to their lives or properties, and not in 1948-49, when the Zionist leadership went out of its way to articulate its desire for peaceful coexistence with the country’s Arab population. Indeed, no sooner had the guns fallen silent than a senior British diplomat on a fact-finding mission to Gaza in June 1949 was told by the refugees that “they have no quarrel with the Jews, that they have lived with the Jews all their lives and are perfectly ready to go back and live with them again.”[25]

These were no idle words. In accepting the partition resolution, the Zionist movement acquiesced in the principle of a two-state solution and all subsequent deliberations were based on the assumption that Palestine’s Arabs would remain as equal citizens in the Jewish state that would arise with the termination of the British mandate. In the words of David Ben-Gurion, soon to become Israel’s first prime minister: “In our state, there will be non-Jews as well—and all of them will be equal citizens; equal in everything without any exception; that is: The state will be their state as well.”[26]

In line with this conception, committees laying the groundwork for the nascent Jewish state discussed in detail the establishment of an Arabic-language press, the improvement of health in the Arab sector, the incorporation of Arab officials in the government, the integration of Arabs within the police and the ministry of education, and Arab-Jewish cultural and intellectual interaction.[27] No less importantly, the military plan of the Hagana (the foremost Jewish underground organization in mandatory Palestine) for rebuffing an anticipated pan-Arab invasion (or Plan D) was itself predicated, in the explicit instructions of Israel Galilee, the Hagana’s commander-in-chief, on the “acknowledgement of the full rights, needs, and freedom of the Arabs in the Hebrew state without any discrimination, and a desire for coexistence on the basis of mutual freedom and dignity.”[28]

The same principle was enshrined in Israel’s Declaration of Independence of May 14, 1948, which undertook to “uphold absolute social and political equality of rights for all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race, or sex” and urged the Arab citizens “to take part in the building of the state on the basis of full and equal citizenship and on the basis of appropriate representation in all its institutions, provisional and permanent.” In its first meeting two days later, the provisional Israeli government discussed a basic law regulating the nascent state’s ruling institutions and practices, which ensured, among other things, the right of Arab citizens to be elected to parliament and to serve as cabinet ministers as well as the continued functioning of the autonomous Muslim (and Christian) religious courts that had existed during the mandate. Four months later, the government decided that Arabic, alongside Hebrew, would serve as the official language in all public documents and certificates.[29]

Had the Palestinian leadership and the neighboring Arab regimes similarly accepted the partition resolution rather than attempt to destroy the state of Israel at birth, there would have been no war and no refugee problem in the first place. Most of mandatory Palestine’s Arab population would have resided in the prospective Arab state and a substantial Arab minority would have lived peacefully in Israel. Hence, the Palestinian exodus was not a result of “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” but a corollary of a failed war of annihilation against a peaceful neighbor.

Likewise, the Palestinian flight during the 1967 war was not the consequence of a “well-founded fear of being persecuted.” The Israeli defeat of the second pan-Arab attempt to destroy it in a generation posed no threat to the West Bank’s civilian population. Quite the contrary, had it been up to Israel, war would not have come to this front in the first place as evidenced by the secret pleas to King Hussein noted above. Besides, with West Bank fighting over within a mere four days, it was clear to all that there was no Israeli plan to harm, let alone expel the Palestinian population in this territory.

Inflating Refugee Numbers

Apart from recognizing the Palestinians as refugees despite their failure to meet the basic criteria for this status and assigning a distinct agency to tend to their affairs, the U.N. blindly registered countless false claimants as refugees despite its keen awareness of the pervasiveness of this fraud, then let their falsely obtained status be passed on to future generations.

At the beginning of August 1948, after eight months of Arab-Jewish fighting, the director of the U.N. Disaster Relief Project (DRP) in Palestine, Sir Raphael Cilento, set the number of refugees at 300,000-350,000,[30] and the September 16 General Assembly report by the U.N. mediator for Palestine Folke Bernadotte settled on the slightly higher figure of 360,000.[31] A supplementary report submitted a month later by Bernadotte’s successor, Ralph Bunche, raised the figure to 472,000, estimating the number of people who would require U.N. aid in the 9-month period from December 1, 1948 to August 1, 1949, at 500,000.[32]

By now, however, the Arabs had dramatically upped the ante. In October 1948, the Arab League set the number of refugees at 631,967, and by the end of the month, official Arab estimates ranged between 740,000 and 780,000. When the U.N.'s Relief for Palestine Refugees began operation in November 1948, it found some 940,000 refugees on its relief rolls.[33]

U.N. officials deemed these figures to be grossly exaggerated, not least since there had been no major influx of refugees since Bernadotte and Bunche submitted their far lower estimates. By way of illustrating the inflated Arab figures, Cilento pointed to allegations of growing refugee presence in certain locations at a time when their real numbers in these sites had actually decreased.[34] Similarly, in his October report, Bunche noted the false allegation by the Syrian authorities of the existence of 30,000 refugees in the northern cities of Aleppo, Latakia, Hama, and Homs whereas the actual figure was hardly half that size.[35] Sir John Troutbeck, head of the British Middle East office in Cairo, got a firsthand impression of the pervasive inflation of refugee numbers during a fact-finding mission to Gaza in June 1949. He reported to London:

The Quakers have nearly 250,000 refugees on their books. … They admit, however, that the figures are unreliable, as it is impossible to stop all fraud in the making of returns. Deaths for example are never registered nor are the names struck off the books of those who leave the district clandestinely. Some names, too, are probably registered more than once for the extra rations.[36]

many cases of death, especially in rural areas, have not been reported. These omissions (which are mainly due to the attempt to obtain food rations of deceased persons) seriously impair the reliability of the death rates (particularly infant mortality rates) and that of the rate of natural increase.[38]

Indeed, the interim report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East of November 16, 1949, which formed the basis for UNRWA’s creation three weeks later, recommended that the number of rations issued by UNRPR “should be reduced by 1 January 1950 from the present rate of 940,000 to 652,000.”[40] Yet, while conceding the impossibility to exclude fraudulent individuals and groups from its refugee rolls, in part given the outpouring of destitute non-Palestinian Arabs seeking to enroll in its services, UNRWA not only refused to reduce refugee numbers below 800,000 but subsequently raised this figure to one million. In the agency’s first year of operation, the number of “refugees” housed in its camps grew by 20 percent with “many thousands of new applications … received each month.” These included new arrivals from Israel—well over a year after the end of hostilities—and “some considerable movement of the [non-Palestinian] population in the search of water, particularly in Jordan, as a result of the severe drought that has dried up wells and cisterns.”[41]

From Transience to Permanence

UNRWA was established on a very precise, highly limited, and short-term mandate:

(a) To carry out in collaboration with local governments the direct relief and works programmes as recommended by the Economic Survey Mission;

(b) To consult with the interested Near Eastern Governments concerning measures to be taken by them preparatory to the time when international assistance for relief and works projects is no longer available.[42]

would increase the productive capacity of the countries in which they have found refuge … halt the demoralizing process of pauperization, outcome of a dole prolonged … [and] increase the practical alternatives available to refugees, and thereby encourage a more realistic view of the kind of future they want and the kind they can achieve.[45]

Nothing of the sort happened. In his first report to the General Assembly in October 1950, five months after its launch, the UNRWA director recounted a smaller reduction in rations distribution and lower employment rates than envisaged by the Economic Survey Mission, with only 17,500 refugees working on new projects. The director attributed this underperformance to UNRWA’s later than expected start of operation; to the unsatisfactory economic conditions in certain areas; and to the difficulty in “selling” the works program to the Arab governments and the refugees. Blaming the United Nations and the West for their plight, the refugees showed “little, if any, gratitude for the Agency’s efforts to maintain or improve [their] condition” instead demanding “increased medical and educational services and improved rations both in quantity and quality.”[47]

Yet rather than seek to dispel this misguided sense of victimized entitlement and steer the refugees toward rehabilitation as stipulated by its mandate, UNRWA began edging in the opposite direction. While paying lip service to its obligation to help “the Near East countries assume responsibility for administering the refugee programme,” it proposed the continuation of direct relief beyond 1950 (budgeting its operations until July 1952) and the effective transformation of the works program into a relief operation “specifically directed toward improvement of the refugees’ living conditions, current and future.”[48] By 1956, its original mission of reintegration had been all but abandoned.[49]

No less importantly, the director’s report absolved the Arab states (let alone the Palestinian leadership) of responsibility for reintegrating the refugees as stipulated by UNRWA’s mandate. While the Economic Survey Mission sought to strengthen the governing and administrative capabilities of the Arab states by empowering them to execute the works programs “to the fullest degree possible,” with the international community reduced to advisory and supervisory roles, the director declared this endeavor “to be beyond the present capacity of Near Eastern governments to bear.”[50] Instead, he insisted that “the magnitude of and the danger inherent in the Near East refugee problem needs the fullest understanding and support of the nations of the world”[51]—this at a time when millions of refugees elsewhere received no international support whatsoever.

What makes this instantaneous dereliction of duty particularly galling is that UNRWA had an excellent example of how to execute its mission. The 48,000 displaced persons in Israel—17,000 Jews and 31,000 Arabs—who initially fell under its jurisdiction were absorbed into Israel’s socioeconomic structures as fully-fledged citizens within a few months in stark contrast to their Palestinian counterparts whose refugee status has been perpetuated for generations. In their discussions with UNRWA, the Israelis rejected the idea of international relief distribution altogether, considering it to be the state’s responsibility to care for displaced persons, especially the aged and infirm among them, through its normal social welfare machinery,[52] which is precisely what was envisaged by UNRWA’s own mandate.

It is true that the scope of Israel’s refugee problem was numerically much smaller than its Palestinian counterpart, yet its relative burden was three time heavier: The 48,000 displaced persons constituted 6 percent of Israel’s total population while the 600,000 Palestinian refugees accounted for a mere 2 percent of the Arab states’ population. And this figure does not include the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees expelled from the Arab states during and after the 1948-49 war—whose numbers exceeded Israel’s total population—who were also absorbed by the Jewish state.

Conclusion

In late 1949, the American Friends Service Committee, which had shouldered most of the Palestinian refugee relief in Gaza, informed the U.N. of its intention to end its operation at the earliest possible moment:

It is obvious that prolonged direct relief contributes to the moral degeneration of the refugees and that it may also, by its palliative effects, militate against a swift political settlement of the problem.[53]

It is true that culpability for this dismal state of affairs is not UNRWA’s alone. With the partial exception of Jordan, which integrated the 1948-49 escapees as full citizens (which should have ended their refugee status), the Arab governments kept the refugees in squalid camps for decades as a means of extracting financial international aid, derogating Israel in the eyes of the West, and arousing pan-Arab sentiments.

Nor were the refugees themselves eager to substitute gainful employment for welfare support. Considering the U.N. to be “entirely responsible for both [their] past and present misfortunes,” they viewed its aid programs as their natural right and were loath to lose its considerable benefits. In the words of UNRWA’s director:

It is probably true to say that the refugees are physically better off than the poorest levels of the population of the host countries; and in some cases better off, in the way of social services, than they were in Palestine.[55]

Yet it is precisely this misguided sense of victimized entitlement and total absence of self-criticism that have turned generations of Palestinian “refugees” into passive welfare recipients rather than productive and enterprising free agents, thus allowing the decades-long manipulation of their cause by successive Palestinian leaderships and the Arab regimes. This in turn means that neither UNRWA, nor the Palestinian Authority, nor the Arab states, nor even the “refugees” themselves are likely to initiate a real change to this state of affairs, which has long benefitted their self-serving interests in one way or another.

One can only hope, therefore, that as UNRWA nears its seventieth anniversary, the agency’s main donors, first and foremost the United States and the European Union, which bankroll nearly half of its budget,[56] will find the necessary courage and integrity to acknowledge the urgency of deep reform and condition future contributions on UNRWA’s reversion to the original mandate: that is, its gradual transfer of responsibility for the Palestinian “refugees” to the Palestinian Authority and the host Arab governments, thus ending their eternal “refugeedom” and facilitating their integration in their respective societies as equal and productive citizens. This will be seventy years later than originally conceived, but better late than never.

Efraim Karsh, editor of the Middle East Quarterly, is emeritus professor of Middle East and Mediterranean studies at King’s College London and director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University.

Notes

[1] “About Us: Figures at a Glance,” U.N. High Commissioner’s Office for Refugees (UNHCR), New York.

[2] “General Assembly Resolution 302. Assistance to Palestine Refugees,” United Nations, A/RES/302 (IV), Dec. 8, 1949, art. 6

[3] See, for example, “The Integration of Refugees into German Life. A Report of the ECA Technical Assistance Commission on the Integration of Refugees in the German Republic, Submitted to the Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Mar. 21, 1951"; Malcolm J. Proudfoot, European Refugees: 1939-52. A Study in Forced Population Movement (London: Faber, 1956)

[4] “About Us: Figures at a Glance,” UNHCR; “Who We Are,” United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA); Programme Budget 2016-2017, UNRWA, Aug. 2015

[5] Deborah Kaplan, The Arab Refugees: An Abnormal Problem (Jerusalem: Rubin Mass, 1959), pp. 118-19, 124; Mrs. Roosevelt at the General Assembly’s 4th sess., 3rd comm., “Refugees and stateless persons,” Lake Success, N.Y., Nov. 12, 1949, p. 132

[6] “Assistance to Palestine Refugees. Interim Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” General Assembly Official Records, 5th sess., supplement no. 19, (A/1451/Rev.), Oct. 6, 1950, art. 6.

[7] “Report of the commissioner-general,” UNRWA, July 1, 1970-June 30, 1971, UNGA A/8413, fn. 1.

[8] “Constitution of the International Refugee Organization,” The Yearbook of the United Nations, 1946-47, pp. 810, 816-17.

[9] David Barnett and Efraim Karsh, “Azzam’s Genocidal Threat,” Middle East Quarterly, Fall 2011, pp. 85-8.

[10] Trygve Lie, In the Cause of Peace. Seven Years with the United Nations (New York: Macmillan, 1954), pp. 162-3.

[11] Constitution of the International Refugee Organization, p. 806.

[12] “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Done in Geneva on 28 July 1951,” Collection of International Instruments Concerning Refugees (Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNCHR, 1979), art. 1/A (2).

[13] UNHCR Resettlement Handbook (Geneva: UNHCR, 2011), p. 19 (emphasis in the original).

[14] Joseph B. Schechtman, Postwar Population Transfers in Europe, 1945-1955 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1962); Schechtman, Population Transfers in Asia (New York: Hallsby Press, 1949).

[15] General Assembly, 4th sess., 3rd comm., meeting 260, Nov. 11, 1949, pp. 124-5; see, also, meeting 258, Nov. 9, 1949; meeting 259, Nov. 10, 1949; meeting 261, Nov. 12, 1949; meeting 262, Nov. 14, 1949; meeting 263, Nov. 15, 1949; meeting 264, Nov. 15, 1949.

[16] Efraim Karsh, “How Many Palestinian Arab Refugees Were There?” Israel Affairs, Apr. 2011, pp. 224-46; “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” Chairman of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, submitted to the U.N. General-Secretary, Nov. 16, 1949, p. 18.

[17] “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,” UNHCR, art. 1-D, p. 16.

[18] “Interim Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” Oct. 6, 1950, art. 15.

[19] Constitution of the International Refugee Organization, Annex I, 1(d), p. 815.

[20] “Progress Report of the United Nations Acting Mediator for Palestine Submitted to the Secretary-General for transmission to the Members of the United Nations,” (Supplement to Document A/648, Part Three), A/689, Oct. 18, 1948, Appx. B, p. 3.

[21] Constitution of the International Refugee Organization, sect. D (b), p. 817; “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,” arts. 1/C (3), 1/E.

[22] Kaplan, The Arab Refugees, p. 129.

[23] See, for example, Michael Oren, Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East (New York: Ballantine Books, 2002), p. 184.

[24] “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,” art. 1/A (2).

[25] Sir J. Troutbeck, “Summary of General Impressions Gathered during Week-End Visit to the Gaza District,” June 16, 1949, The National Archives, London, FO 371/75342/E7816, p. 123.

[26] David Ben-Gurion, Bama’aracha (Tel Aviv: Mapai Publishing House, 1949), vol. 4, part 2, p. 260. Ben-Gurion reiterated this pledge on May 4, 1948, ten days before the proclamation of Israel: “We hope to have soon a free parliament in the state of Israel, democratically elected by all its citizens: all the Jewish citizens and all Arab citizens who would like to remain in Israel.” David Ben-Gurion, Behilahem Israel (Tel Aviv: Mapai Publishing House, 1951; 3rd ed.), p. 102.

[27] See, for example, protocol of the Situation Committee’s meetings on Nov. 24 and Dec. 22, 1947, Ben-Gurion Archive, Sde Boker; protocol of the subordinate Committee C meetings on Dec. 1, 2, 22, 1947, Ben-Gurion Archive; Secretariat of Subordinate Committee B, “Proposal for the establishment of a Police in the Hebrew State,” Dec. 31, 1947, Ben-Gurion Archive.

[28] Hagana commander-in-chief to brigade commanders, “Haarvim Hamitgorerim Bamuvlaot,” Mar. 24, 1948, Hagana Archive, Tel Aviv, HA/46/199z.

[29] “Protocol of Israel’s Provisional Government Meeting,” Israel State Archive (ISA), Jerusalem, May 16, 1948, pp. 11-18, 20; Protocol of the Provisional Government Meeting, ISA Sept. 5, 1948, p. 5.

[30] “Disease Threatens Refugees,” The New York Times, Aug. 3, 1948.

[31] “Progress Report of the United Nations Mediator on Palestine Submitted to the Secretary-General for Transmission to the Members of the United Nations in Pursuance of Paragraph 2, Part II, of Resolution 186 (S-2) of the General Assembly of 14 May 1948,” U.N. General Assembly, General Assembly Official Records: 3rd sess., suppl. no. 11 (A/648), Sept. 16, 1948, p. 78.

[32] “Progress Report of the United Nations Acting Mediator for Palestine,” pp. 2-3, 8.

[33] “Refugees Put at 700,000,” The New York Times, Aug. 17, 1948; “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” p. 17; Rony E. Gabbay, A Political Study of the Arab-Jewish Conflict. The Arab Refugee Problem (A Case Study) (Geneva: Librairie E. Droz, 1959), pp. 167-8; W. de St. Aubin, “Peace and Refugees in the Middle East,” Middle East Journal, July 1949, p. 251.

[34] Beirut to Foreign Office, Oct. 1, 3, 1948, FO 371/68679.

[35] “Progress Report of the United Nations Acting Mediator for Palestine, Appx. A, p. 3.

[36] Troutbeck, “Summary of General Impressions.”

[37] “Explanatory Note,” Village Statistics 1945 (Jerusalem: Palestine Office of Statistics, 1945), p. 2 (A5).

[38] Government for Palestine, Supplement to Survey of Palestine: Notes compiled for the information of the United Nations Special Committee of Palestine (London: HMSO, June 1947; reprinted in full permission by the Institute for Palestine Studies, Washington, D.C.), p. 14.

[39] Ibid., pp. 10-11; “The Palestinian Refugee Problem (Report No. 3),” Israeli Foreign Ministry, Middle East Dept., Feb. 2, 1949, Israel State Archives, FM 347/23; Israeli Foreign Ministry, “Notes on Arab Refugees, the Boundaries of Israel, and Jerusalem,” Aug. 22, 1949, FM 347/23; Walter Pinner, How Many Arab Refugees? A Critical Study of UNRWA’s Statistics and Reports (London: MacGibbon and Kee, 1959), part III.

[40] “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” p. 17

[41] “Interim Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” Oct. 6, 1950, arts. 13, 14, 16; “Assistance to Palestine Refugees: Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” General Assembly Official Records: 6th sess., suppl. no. 16 (A/190), Sept. 28, 1951, “Foreword,” art. 28.

[42] “General Assembly Resolution 302. Assistance to Palestine Refugees,” art. 7.

[43] “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” pp. 14-15.

[44] “194 (III). Palestine - Progress Report of the United Nations Mediator,” General Assembly, A/RES/194 (III), Dec. 11, 1948, art. 11.

[45] “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” pp. 16-17.

[46] Ibid., p. 17.

[47] “Interim Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” Oct. 6, 1950, arts. 26, 28, 29, 41-4.

[48] Ibid., arts. 65, 67, 76.

[49] Edward H. Buehrig, The UN and the Palestinian Refugees: A Study in Nonterritorial Administration (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1971), p. 122.

[50] “First Interim Report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East,” p. 18.

[51] “Interim Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” Oct. 6, 1950, arts. 74, 76, 79, 83.

[52] Ibid. arts. 30-1.

[53] Asaf Romirowsky and Alexander H. Joffe, Religion, Politics, and the Origins of Palestine Refugee Relief (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2013), p. 88.

[54] United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, “Final report of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East” (Lake Success, N.Y.: United Nations, Dec. 28, 1949), “Introduction,” p. vii.

[55] “Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,” Sept. 28, 1951, arts. 34-6.

[56] Governments and EU Pledges to UNRWA (Cash and In-kind) for 2015 – Donor Ranking in USD AS 31 December 2015, UNRWA.