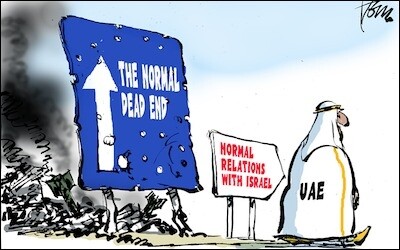

The new accord under which the United Arab Emirates and Israel are normalizing relations marks a major shift in Israel’s dealings with the Gulf states and in the region in general. Brought about with support from the Trump administration, the deal will help cement the legacies of President Donald Trump, Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu, and the U.A.E.'s Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Zayed. Each country stands to gain something different from the deal: Washington can point to a success at peacemaking, achieving what the Obama administration did not; Abu Dhabi can say it halted Israel’s threat to annex parts of the West Bank; and Jerusalem can point to this as a new milestone in relations with the Islamic and Arab world.

The deal comes in the context of major tectonic shifts in the Middle East. In May, Greece, Egypt, France, Cyprus, and the U.A.E. slammed Turkey over its increasingly aggressive stance in the Mediterranean. Last month, Israel signed an EastMed pipeline deal with Greece and Cyprus. Egypt, a key ally of the U.A.E., recently signed a different Mediterranean agreement with Greece delimiting maritime jurisdictions. In addition, in July two Israeli defense companies signed a deal to work with a U.A.E.-based company to find solutions in the fight against COVID-19. There has also been an increase in humanitarian-aid flights between the U.A.E. and Israel, despite the countries’ having no existing relations till now. The picture being painted is of a closer alliance among Israel, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, and the U.A.E.

The agreement with Abu Dhabi is the first big peace push since the Oslo Accords.

The agreement with Abu Dhabi is the first big peace push in the decades since the Oslo Accords, which Israel and the Palestinians signed in the 1990s. It’s important to recall that when Israel was founded in 1948, its immediate Arab neighbors were not only hostile but launched an invasion. Israel initially had relations with states in the wider Muslim world, such as Iran and Turkey. Today the situation is reversed. Egypt signed a peace deal with Israel in 1979, and Jordan followed in 1994. Israel also quietly sought low-level ties with Morocco, Tunisia, and other Gulf states such as Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, and the U.A.E. Israel and Qatar are in frequent contact to calm tensions in Qatar-funded, Hamas-run Gaza.

In contrast to previous eras in which Israel’s greatest enemies were the Arab states, today Israel’s greatest adversary is Iran. In addition to stockpiling missiles and building up its nuclear program, the Iranian regime supports Shiite groups in Iraq, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Syrian dictatorship, and Houthi rebels in Yemen — all threats to Israel. The Houthis, whose official slogan includes the phrase “death to Israel, curse the Jews,” are currently fighting Saudi Arabia and have also fought U.A.E.-backed forces. Given Iran’s role in the region, an alliance system linking Jerusalem, Abu Dhabi, and Riyadh is clearly in their common interests.

Turkey is also a leading opponent of Israel today, despite diplomatic relations dating back to the 1950s. Turkey slammed the U.A.E. deal and threatened to break off relations with the Gulf state. Hours before Israel’s deal with the U.A.E. was announced, Netanyahu said Israel was siding with Greece in its recent tensions with Turkey.

Israel and the U.A.E. will effectively complement each other’s strengths.

As this alliance system grows, Israel and the U.A.E. will effectively complement each other’s strengths. The two countries have among the highest GDP per capita in the Middle East. Israel is a leader in defense technology, such as the Iron Dome air-defense system, and the U.A.E. is a center of global commerce. With more open relations, these two dynamic economies could become a regional powerhouse. For that to happen, the U.A.E. will have to overcome attempts by Turkey and Iran to sabotage the deal. Netanyahu will have to sideline his governing coalition’s more extreme right wing and religious supporters, who prefer annexing the West Bank to ties with an Arab state.

The Israel–U.A.E. accord is only the beginning of a new strategic consensus in the region.

The Israel–U.A.E. accord is only the beginning of a deepening relationship and new strategic consensus in the region. It came about in the shadow of the threats posed by the Iran Deal and with support from the Trump administration. A political transition in the U.S. may affect this new entente, and it may be challenged by further tensions with Iran, Turkey, and terror groups like Hamas and Hezbollah. For now, the Israel–U.A.E. agreement looks to accelerate a warming trend, ending decades of stagnation in Israel’s diplomatic relations in the Middle East. It points to a new strategic relationship for Jerusalem and several of the Arab states.

Seth Frantzman is a Ginsburg-Milstein Writing Fellow at the Middle East Forum and senior Middle East correspondent at The Jerusalem Post.