While Christians make up less than half a percent of Turkey’s population, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his ruling Justice and Reconciliation Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) depict them as a grave threat to the stability of the nation. With Erdoğan’s jihadist rhetoric often stereotyping Christian Turkish citizens as not real Turks but rather as Western stooges and collaborators, many Turks seem to be tilting toward an “eliminationist anti-Christian mentality,” to use historian Daniel Goldhagen’s term. Small wonder that the recent launch of an official online genealogy service allowing Turks to trace their ancestry has kindled a tidal xenophobic wave on the social media welcoming the fresh possibility to expose “Crypto-Armenians, Greeks, and Jews” mascarading as true Turks. [1]

“The Mosques Are Our Barracks”

Persecution of Turkey’s Christian minority has long predated Erdoğan and the AKP. As it stood on the verge of extinction, the Ottoman Empire engaged in mass deportations and massacres that culminated in the Armenian genocide. The end of World War I saw the expulsion of more than a million Greeks,[2] and the position of the dwindling Christian community only somewhat improved in Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s secularist republic. Yet while Kemalist Turkey paid lip service to the equality of its non-Muslim minorities, the AKP unabashedly excludes these groups from Turkey’s increasingly Islamist national ethos.[3]

An ominous indication of what lay in store for the religious minorities was afforded as early as December 1998 when Erdoğan, then mayor of Istanbul and an opposition politician, announced that the “mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets, and the faithful our soldiers,” quoting a line from a poem by the nineteenth-century nationalist poet Ziya Gökalp underscoring the Islamist foundation of Turkish identity. And while this recitation landed Erdoğan in prison for inciting religion-based hatred,[4] once at the helm, he steadily realized this vision, systematically undoing Atatürk’s secularist legacy and Islamizing Turkey’s public space through such means as the government-operated Religious Affairs Directorate (Diyanet), which pays the salaries of the country’s 110,000 imams and controls the content of their Friday sermons.

Things came to a head during the July 15, 2016 abortive coup when the regime ordered the imams to go to their mosques and urge the faithful to take to the streets to quash the attempted revolt.[5] Not surprisingly, this Islamist-nationalist reassertion was accompanied by numerous Christophobic manifestations (in Ayyan Hirsi Ali’s words),[6] notably attacks on churches throughout the country.[7] In Malatya, for example, a gang chanting “Allahu Akbar” broke the glass panels of the front door of a Protestant church while, in the Black Sea city of Trabzon, rioters smashed the windows of the Santa Maria Catholic church. Witnesses said the attackers used hammers to break down the door of the church before Muslim neighbors drove them away.[8] As Istanbul pastor Yüce Kabakçı lamented:

The reality is that Turkey is neither a democracy nor a secular republic. There is no division between government affairs and religious affairs. There’s no doubt that the government uses the mosques to get its message across to its grassroots supporters. There is an atmosphere in Turkey right now that anyone who isn’t Sunni is a threat to the stability of the nation. Even the educated classes here don’t associate personally with Jews or Christians. It’s more than suspicion. It’s a case of let’s get rid of anyone who isn’t Sunni.[9]

Anti-Christian incitement continued apace after the coup. In February 2017, Turkey’s Association of Protestant Churches released its annual “Rights Violation Report,” which claimed that anti-Christian hate speech had increased in Turkey in both social and conventional media, reaching extreme levels during the 2016 Christmas season. Churches in particular faced serious terror threats with the government doing little to stop these open Christophobic displays.[10]

On December 28, 2016, for example, in the western province of Aydin, the ultra-nationalist Islamist group Alperen Hearths staged a forced conversion of Santa Claus to Islam, putting a gun to the head of an actor dressed as Santa Claus. A representative of the group explained the staging of the conversion this way:

Our purpose is for people to go back to their roots. We are the Muslim Turkish people who have been leading Islam for thousands of years. We will not celebrate Christian traditions and disregard our own traditions like Hıdrellez, Nevruz, and other religious national holidays.[11]

It is easy to dismiss such events as mere talk. However, in Muslim-majority states, notably Egypt, Christmas and New Year’s Eve celebrations often form the scene of murderous attacks.[13] So it was in Turkey on December 31, 2016, when an ISIS-affiliated terrorist wearing a Santa hat sprayed gunfire at a mixed group of foreigners and Turks enjoying their 2017 New Year’s celebration at an Istanbul nightclub, killing 39 people and wounding another 69.[14] In an editorial in The Guardian on January 3, 2017, Turkish novelist Elif Shafak described the rising anti-Western fanaticism as unnerving:

Those who question the party line are labeled “betrayers” and “pawns” of Western powers. Young people are told that we are a country surrounded by water on three sides and enemies on all four. As paranoia, distrust, and fear intensify, the culture of coexistence dissolves.

A State-sponsored Conspiracy Theory

The post-coup anti-Christian rhetoric has tended to follow a familiar pattern, namely that Christian Turkish citizens are not real Turks but are instead loyal to the West. The rhetoric conflates many different streams of Western thought: The secular reveler who embraces the New Year’s tradition and the pious Christian who celebrates Christmas are equally suspect. Such rhetoric would not be quite so dangerous if the Turkish media offered a counterargument, but with the government’s mass incarceration of all those remotely critical of the AKP and Erdoğan, it is unlikely that any viable alternative will be presented to the Turkish public.

According to Voice of America News, in the months following the coup, many pro-government media outlets and some government officials directly accused the West, Christians, and Jews of having played a role in it. For example, at a pro-government “Democracy and Martyrs” rally in August, attended by more than a million people, speakers linked religious minorities to the coup plotters, calling them “seeds of Byzantium,” “crusaders,” and a “flock of infidels.”[16] Human rights lawyer Orhan Kemal Cengiz said pro-government media have:

embraced an alarming narrative of scapegoating Turkey’s religious minority and connecting the coup plot to them … Particularly pro-government media outlets have taken an anti-U.S. and anti-EU attitude, which I can call a xenophobic attitude, in which they attempt to demonize the West and accuse it of the coup attempt. And this narrative targets and harms non-Muslims in Turkey.[17]

While the idea that Christian Turks are collaborators with the West is nothing new, the uncritical mass acceptance of such a narrative has exacerbated the coup’s effect on Turkey’s Christian minority. According to American anthropologist Jenny White, the educational system in Turkey has for years promoted a distrustful view of Christian Turks and the predominantly Christian West. This perception of Christian Turks as the “other” can best be understood by reviewing the curriculum of security courses that were mandatory for all high school students from 1926 until January 2012. Taught by active or retired military officers appointed by the local military base, such courses articulated the idea that Turkey has no friends and that no country in the world wants it to be strong. Security textbooks often presented non-Sunni citizens as divisive, internal elements supported by Turkey’s enemies.[18] A similarly stark picture is painted by anthropologist Ayşe Gül Altınay. Having observed classrooms around the country, Altınay found almost no discussion of peace, coexistence, dialogue, or nonviolence. Instead, students were taught to fear differences and to treat their non-Muslim friends as decidedly the “other.”[19]

Turkey’s school system has been used as a political arm of the state ever since Atatürk founded the Turkish republic in the 1920s, and the AKP has gradually shifted the system away from its secularist roots. In July 2017, for example, Education Minister Ismet Yılmaz declared that Turkish public schools would no longer teach Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Instead, the concept of jihad would be added to the religious teaching curriculum beginning with the 2017-18 academic year, and schools would be required to teach the concept as patriotic in spirit. As Yılmaz told reporters:

It is our duty to fix what has been perceived as wrong. This is why the Islamic law class and basic fundamental religion class will include [lessons on] jihad. Loving your nation is the real meaning of jihad.[20]

In a further indication of this trend, the Syrian Christian co-mayor of Mardin was asked to step down from her post by the Turkish government in November 2017. Likewise, the Turkish authorities removed an Assyrian sculpture from a public square in front of the local council building in Diyarbakir. No explanation was given for the removal of either the sculpture or the co-mayor, who was replaced by an official appointed by the government.[22]

In reality, the alleged threat that Turkey could become a Christian nation is readily belied by the country’s demographics, especially when looking at changes in domestic religious affiliation over the past century. According to the Ottoman census, Turkey’s Christian minority was just under 20 percent of the population in 1914. By 1927—a mere thirteen years later—Christians made up less than 2.5 percent of the population. Today Christians make up less than 0.2 percent of Turkey’s population of 80 million. (Included in that number are an estimated 45,000 Christian refugees fleeing ISIS persecution in Iraq and Syria.[23]) In fact, even the puny 0.2 percent estimate may be a little high. The official census puts Islam at 99.8 percent of the adopted religion of Turks and 0.2 percent as “other” (mostly Christians and Jews).[24]

New Obstacles to Worship

Like other Islamic-majority states, the rights of Christians in Turkey have never been the same as those of the Muslim majority—not in the Ottoman Empire and not today. Modern-day laws remain biased in favor of Muslims. Church buildings are not allowed to be taller than certain heights while enormous mosques are built on the highest hilltops. Christian worship services are only permitted in “buildings created for the purpose.” Turks who openly discuss Christianity face harassment, threats, and imprisonment. Most churches are surrounded by high walls and protected by 24-hour guards.[25]

Even so, Turkish Christians and other minorities noted a qualitative change in the tenor of the Sunni majority’s attitude toward them after the 2016 coup. According to Ian Sherwood, the chaplain of the British consulate and the priest of the Crimean Memorial Church:

There is a rising undercurrent of intolerance toward Christians and other non-Muslims in Turkey and this goes further than boys standing on the walls of [the] churchyard shouting “Allahu Akbar.” We Anglicans have been here since 1582 and yet we’re not able to build churches except for a short period in the nineteenth century. And now it’s very rare that you hear of a Christian community being able to build a church.[26]

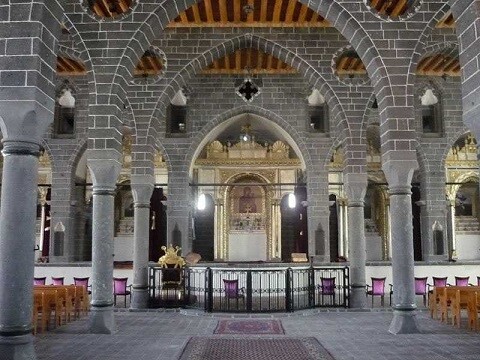

In some cases, the government or local town councils have appropriated the church property of Christian Turks. In April 2016 for example, the authorities seized all the churches in the majority Kurdish southeastern city of Diyarbakir. The historic Armenian Surp Giragos Church, a 1,700-year old church and one of the largest Armenian churches in the Middle East, was seized by the government.[29] And while the government justified the move by the need to rebuild and restore the city’s historic center after ten months of bitter fighting against the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party, Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan), many within the Christian community were skeptical of the explanation. The Diyarbakir Bar Association, representing Christians worshipping at one of the churches, filed an appeal over the action.[30]

The Turkish government also recently seized multiple properties in the southeastern city of Mardin belonging to Assyrian (Syrian) Christians and transferred them to public institutions: Dozens of churches and monasteries were reassigned to the Diyanet; cemeteries were transferred to the metropolitan municipality.[31] This seizure of church property is one of many indications that the government does not view Christians as part of the broader Turkish community.

A New Genocide?

For some religious minorities, these confiscations bring back bitter memories. A little over a century ago, in 1915, the Ottoman Empire’s Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) passed legislation authorizing the deportation of “persons judged to be a threat to national security.” Deportees, many of whom were Armenian Christians, were instructed not to sell their assets but rather to provide a detailed list of what they owned:

Leave all your belongings—your furniture, your beddings, your artifacts. Close your shops and businesses with everything inside. Your doors will be sealed with special stamps. On your return, you will get everything you left behind. Do not sell property or any expensive item. Buyers and sellers alike will be liable for legal action. …You have ten days to comply with this ultimatum.[32]

A century later, Turkey’s civil codes still give the executive far-reaching powers to confiscate property on the basis of protecting “the national unity” of the Turkish republic.[35]

Conclusion

Under Erdoğan’s leadership, especially after the 2016 coup, Turkey’s religious minorities find themselves marginalized and isolated from the Sunni majority. Anti-Western and anti-EU rhetoric often morphs into rabid anti-Christian incitement with the clear message that the country’s Christian citizens are not true Turks, a message that the state-controlled media and government officials have either actively promoted or refused to denounce. Exacerbated by government policies such as the addition of jihad teaching to the school curriculum, these measures place Turkey’s non-Muslim minorities in an increasingly precarious situation.

Anne-Christine Hoff is an assistant professor of English at Jarvis Christian College in Hawkins, Texas.

Notes

Fehim Taştekin, “Turkish genealogy database fascinates, frightens Turks,” al-Monitor (Washington, D.C.), Feb. 21, 2018.

Renée Hirschon, ed., Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey (Oxford: Berghan, 2003), p. 6.

John Eibner, “Turkey’s Christians under Siege,” Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2011, pp. 41-52; Daniel Pipes, “Dhimmis No More: Christians’ Trauma in the Middle East,” danielpipes.org, Jan. 2018.

Deborah Sontag. “The Erdogan Experiment.” The New York Times Magazine, May 11, 2003.

The New York Times, July 17, 2016; al-Monitor, July 25, 2016.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, “The Global War on Christians in the Muslim World,” Newsweek, Feb. 6, 2012.

The New York Times, Apr. 23, 2016; World Watch Monitor (London), Feb. 7, 2018

The Express (London), Apr. 22, 2016.

Ibid., Aug. 1, 2016.

Turkish Association of Protestant Churches Human Rights Violations Report, 2016, South Hadley, Mass.

Hürriyet Daily News (Istanbul), Dec. 29, 2016.

Elif Shafak, “The Reina atrocity shows how deeply fanaticism has taken hold in Turkey,” The Guardian, Jan. 3, 2017.

See, for example, “A Gruesome Christmas under Islam,” ryamondibrahim.com, Jan. 18, 2016; “Death and Destruction on Christmas: Muslim Persecution of Christians, December 2016,” raymondibrahim.com, Mar. 13, 2017.

The Guardian, Jan. 1, 2017.

Shafak, “The Reina atrocity shows how deeply fanaticism has taken hold in Turkey.”

The National Herald (New York), Sept. 28, 2016.

Voice of America News, Sept. 25, 2016.

Jenny White, Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 80-101.

Ayşe Gül Altınay, “Human Rights or Militarist Ideals? Teaching National Security in High Schools,” in Gürol Irzik, Deniz Tarba Ceylan, and Ismet Akça, eds., Human Rights Issues in Textbooks: The Turkish Case (Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yayınları, 2004), pp. 76-90

The Independent (London), July 18, 2017.

White, Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks, pp. 80-101

Uzay Bulut, “Turkey Uncensored: The Fate of Assyrian Christian Churches and Monasteries,” The Philos Project, New York, July 13, 2017.

“Attacks hint that Christians may fare worse in post-coup Turkey,” Iraqi Christian Relief Council, Glenview, Ill. Aug. 23, 2016.

“Turkey, People and Society,” CIA World Factbook (Washington, D.C.: CIA Office of Public Affairs, Mar. 16, 2018).

“Is Ataturk’s dream of a secular Turkey lost?” Belief Net News (Virginia Beach), accessed Mar. 3, 2018.

Alec Marsh, “The war on Christians is extending into Turkey,” The Spectator, July 19, 2016.

Burak Bekdil, “Red Alert! Protestant Couple ‘Security Threat’ to Turkey!” The Gatestone Institute, New York, Oct. 22, 2016.

Voice of America News, Sept. 25, 2016.

The New York Times, Apr. 23, 2016.

The Express, Apr. 22, 2016.

Agos (Istanbul), June 23, 2017.

Uğur Umit Ungör and Mehmet Polatel, Confiscation and Destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011), p. 69.

Taner Akçam, A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007), p. 86.

Vahagn Avedian, “State Identity, Continuity and Responsibility: The Ottoman Empire, the Republic of Turkey and the Armenian Genocide,” European Journal of International Law, 2013, no. 3, pp. 797-820.

Mehmet Polatel, Beyannamesi: Istanbul Ermeni Vakıflarının el konan mulkeri (Istanbul: Uluslararası Hrant Dink Vakfı Yayınlari, 2012), p. 69.