The global proliferation of jihadist violence over the past decades notwithstanding, many educated Westerners still view this phenomenon as a corollary of an extremist misinterpretation of jihad that has nothing to do with the concept’s purported real meaning (i.e., an inner spiritual battle), or indeed with the actual spirit and teachings of Islam. Yet while the overwhelming majority of the world’s Muslims do not actively support the global jihadist movement, this does not make it a hijacker or distorter of Islam. Rather, both the movement’s pronounced goals and modus operandi arise from or reflect Islam’s authoritative texts, traditions, and history. But understanding this requires greater conceptual clarity about the interrelationship among the three Western categories at the heart of controversy: politics, theology, and religion.

Politics

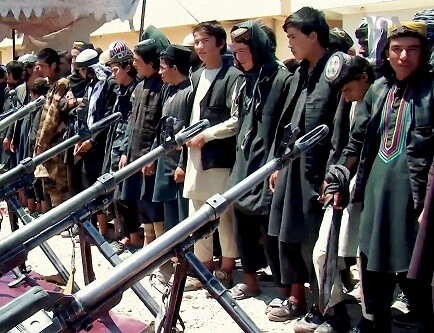

The global jihadist movement is political in two significant and uncontroversial respects. For one thing, it aspires to direct and administer states as ISIS managed to do in parts of Syria and Iraq, albeit briefly. Indeed, jihadists possess what they regard as a unique and efficacious Islamic art of directing and administrating states. For another thing, jihadists seek to acquire political power via violent revolutionary means, primarily insurgency, but supported by terrorism and other tactics.

Jihadist violence, whether directed at Muslim regimes or Western governments and populaces, is therefore political as it seeks to bring Islam to power in territorial states and thus implement its political agenda. Jihadists ultimately aim to redraw or remove boundaries between these states currently sovereign under international law and establish a global caliphate.

In line with Islam’s fundamental outlook, jihadists categorically reject a functional separation between the private-spiritual and public-political spheres of both individual and communal life because of their understanding of two fundamental characteristics of Islam: Islam is both “complete” (kamil), which is to say perfect and sufficient, and “comprehensive” (shamil), encompassing all aspects of human life. As the founder of the Islamist group Hizb at-Tahrir, Taqi ad-Din an-Nabhani, put it, Islam “is a complete and comprehensive regime for the totality of human life, which Muslims are obligated to implement and execute completely.”[1]

So where does this complete and comprehensive conception of Islam, which recognizes no distinction or separation between politics and religion—between thesecular and the sacred—leave the category of “politics” in jihadist thought? The Arabic language does have a word for “politics"—siyasa—that corresponds to the Western category. But siyasa is not a Qur’anic concept, which might explain why it is not a central concept in jihadist literature. There are, on the other hand, several important Qur’anic concepts that feature prominently in jihadist thought that could be described as political in Western terms. These include khalifa (caliph), Shari’a, and the lesser-known term hukm, which means “judgment” or “rule.” Qur’anic passages involving one or more of these concepts appear often in jihadist writing and together form the theological bedrock of jihadist political theory.

Hukm, from the verb hakama (to judge) has the sense of meaning rule in all its political dimensions. The verb hakama, for example, occurs in three closely related Qur’anic passages in the fifth sura (al-Ma’ida, The Table), which are often cited in jihadist literature, particularly in arguments seeking to substantiate the infidel status of governments in today’s Muslim-majority states.

The formula is first found in the last part of verse 42: “Unbelievers are those who do not judge according to God’s revelations.”[2]The passage is repeated with minor variation in verses 45 and 47.[3] Jihadists interpret these as indicating that any ruler who fails to govern in strict accordance with the Shari’a (as they define it) is an infidel and thus to be resisted, including violently, in accordance with their expansive view of apostasy and its penalties.

Khalifa, or caliph, comes from the verb khalafa, which means to follow or succeed. Caliph literally means successor and, in the context of Islam, specifically denotes the successor to the prophet Muhammad, Islam’s first political ruler. The announcement by the Islamic State (ISIS) of its putative caliphate in 2014 provides a vivid illustration of how the Qur’anic concept caliph is used by jihadists in support of their political goals.

The statement was titled “This Is What God Has Promised,”[4] and it begins with verse 55 of Surat an-Nur (The Light), which says:

God has promised those of you who believe and do good works to make them masters in the land as He made those who went before them, to strengthen the Religion. He chose for them, and to change their fears to safety... “Let them worship Me and serve none besides Me. Wicked indeed are they who after this deny Me.”

The verb translated “make masters” (“rulers” in other translations) is istakhlafa from the root khalafa and, therefore, with connotations of caliph.[5] On the basis of this and related Qur’anic passages, the ISIS statement claims that God has promised Islam global leadership and sovereignty over the earth, but that fulfillment of this promise is contingent on God being worshiped in the strictest monotheism. Consequently, paving the way for the fulfillment of God’s political promise is one of the central missions for the global jihadist movement.

This examination of jihadist exegesis illustrates that while jihadists do not formally recognize the Western distinction between politics and religion, they nevertheless have something like a political theory. God rules over the earth as the sovereign through his revealed law in the form of the Shari’a, andthe human political task is to ensure that His sovereign rule is put into effect by subjecting and ordering all human social relations to the arbitration of that revealed law. The apparent contradiction between the inseparability of religion and politics is resolved by recalling that Islam is a complete and comprehensive way of life. For jihadists, Islam is a nidham (regime) and a manhaj (program) that is to be implemented completely in both the private and public spheres. In that sense, jihadist political theory and the political manifesto that flows from it (in the Western sense of political) are simply dimensions of living out Islam.

Fighting jihad, establishing Islamic states, and publicly enforcing Shari’a are connected to personal moral obligations and duties, such as performing the salat—the five daily prayers. All form part of the one regime and program. Tellingly, jihadists often describe jihad as an ibada (worship), a clear indication of how jihad is integrated into a holistic conception and practice of Islam as a mode of life.

The global jihadist movement and its violence is truly a political movement. The question, however, is whether politics alone can provide a complete and comprehensive understanding of the movement and its violence. This brings us to theology.

Theology

Theology, in the Western sense, is not a category in jihadist thought or arguably in Islamic thought. One Arabic term equates to the English word “theology,” ilm al-lahut, but refers exclusively to Christian theology.

Islam, on the other hand, has its own indigenous tradition of scholarship with a unique vocabulary designated by the umbrella term ulum Islamiya (Islamic sciences). These cover a range of disciplines, some with correlates in other faiths, such as tafsir (exegesis) —found also in Judaism and Christianity. Others are particular to Islam, such as hadith science, the study of the prophet’s biography, and asbab an-nuzul, which is the science of determining the sequence and circumstances in which each passage of the Qur’an was revealed since passages within individual suras are not arranged in chronological order.

Still, one can productively employ the Western (or Christian) conception of theology to analysis of the global jihadist movement much in the same way as with politics. This draws out some distinctive characteristics that are not captured by politics and which differentiate the global jihadist movement from secular, political movements with which it is often (misleadingly) compared.

A conventional Christian definition of theology “denotes teaching about God and his relation to the world from creation to the consummation, particularly as it is set forth in an ordered, coherent manner.”[6] In this sense, it is possible to conclude jihadists do have a theology shaping their worldview and political activity.

Introducing the category “theology” also allows one to identify something unique about jihadist political concepts such as caliph, Shari’a, and hukm. They are theological concepts in twin senses that relate to teaching about God and his relation to the world, and they find their source in a text regarded as the literal word of God, which articulates His will for humankind.

Some of the foundational concepts of jihadist thought and activity can thus be described using two distinct Western categories: politics and theology. Put differently, it requires two Western conceptual categories to adequately describe, let alone explain, key aspects of jihadist thought, which combine to form a “political theology.” Central jihadist concepts such as caliphate, Shari’a, and hukm are best thought of as theopolitical concepts that relate both to God’s relation to the world and to the administration of states.

An understanding of global jihadist terrorism illustrates the necessity of integrating politics and theology. The moral legitimation for killing Western citizens is fundamentally theological, based on an interpretation of commandments made by God in the Qur’an and the model of warfare practiced by Muhammad and his successors. But the selection of terrorist targets is often made on the basis of political considerations. Targets are rarely, if ever, selected because of revelation, but rather for their strategic, symbolic, and political value to the larger jihadist political agenda: coming to power and implementing “true” Islamic rule.

Why, then, is it so controversial to talk about theology when it comes to the global jihadist movement and its violence? One explanation is the nature of contemporary social sciences where there is palpable and sometimes explicit discomfort with the category of theology. This can be attributed to what Jason Blum aptly terms the “methodological and ontological naturalism” of most social science researchers, the idea that “phenomena are to be explained solely through natural [mundane, not religious] … categories and causes.”[7]

Methodological and ontological naturalism treats the theology of its subjects as irrelevant because there is no such thing as “God’s relation to the world.” Theological concepts and rhetoric, along with religious practice and experience, are to be explained by natural phenomena and causes alone, which are necessarily ulterior when the subjects claim theological motivations and goals. Politics, unlike theology, is considered to be real, tangible, and, most importantly, natural, and therefore a legitimate category for explaining the global jihadist movement.

There is a tension for social scientists, however, because jihadist literature is saturated in theological language. So researchers must do something with the expressed theology of jihadists. Two strategies are common in academic literature and public commentary. One is to minimize the importance of jihadist theology and then to ignore it. The other is to construe jihadist theology as merely politics by another name.

Thomas Hegghammer, a leading expert on the global jihadist movement, offers a vivid illustration of the “minimize-and-ignore” strategy. While he acknowledges that the movement “has both theological and political dimensions and may be analyzed from both perspectives,” he advocates focusing exclusively on politics because theology, though useful for understanding the “intellectual origin of particular texts,” cannot explain the “political preferences” of jihadists. [8] Jihadists, therefore, have a theology, but one that is not deemed to be particularly illuminating of their violent, revolutionary political agenda.

For his part, French political scientist Olivier Roy, who has published widely on Islamism and Islamist terrorism, contends that jihadist violence arises from what he calls the “Islamization of radicalism” and not the “radicalization of Islam.” He contends that “rebellious youth” have simply “found in Islam the paradigm of their total revolt.”[9] In other words, jihadists are really to be understood as political revolutionaries, who incidentally express their tendencies through Islam, perhaps for reasons of convenience, i.e., they were born into Muslim families and communities.

The evidence, however, forces Roy to use the term “religion” constantly, undermining his thesis that theology is ancillary. He admits that foreign jihadists from France and Belgium appear overwhelmingly to be “born-again” Muslims who, “after living ahighly secular life … suddenly renew their religious observance.” He further concludes that they are “sincere believers.” But he then appears confused by the fact that there is a “paucity of religious knowledge among jihadis. [10] Roy takes this paucity of theological knowledge as evidence that theology is incidental to the revolutionary impulse driving rebellious Muslim youth to violence. This is a clear example of the politics-by-another-name strategy.

Roy’s analysis reflects a common problem among contemporary social scientists: the inability to take professed, or even observable, religious experience seriously, even when these apply to young people who have made the momentous decision to give up their lives to fight and possibly die in the name of Islam.

Another source of controversy relates to Western Muslim scholars, for whom questions about jihadist theology are unavoidably normative. There is much more at stake for Muslim scholars than merely an accurate description of jihadist theology. It is entirely understandable that such scholars wish to dispute the normative theological claims made by jihadists and to offer an alternative reading of those same sources and traditions.

The tension, however, arises from the fact that the global jihadist movement does not pose normative theological questions for non-Muslim scholars, or indeed for the majority of Westerners. Yet some Muslim scholars misconstrue descriptive statements from non-Muslim scholars about contemporary jihadist beliefs as normative statements about Islam as a whole, then oppose such descriptions. They object to non-Muslim scholars adopting the language of jihadists because they believe it unjustly legitimizes jihadists.

Some take this opposition to extremes. Muslim scholar Asma Afsaruddin, for example, has argued that “those who describe the actions of these militant groups as jihad are part of the problem.” She has even provocatively suggested that it is “Islamophobes” who “focus on the notion of jihad as armed combat.”[11] This opposition to even talking about jihadist theology pushes many non-Muslim scholars to the more comfortable and uncontroversial waters of political explanations, which also happen to be those offered by Muslim scholars like Afsaruddin.

But as Sun Tzu famously observed, “If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained, you will also suffer a defeat.”[12] Shutting down honest and empirical study of jihadist thought is utterly counterproductive, a recipe for gross misunderstanding of an enemy with which the West—rightly or wrongly—finds itself at war. Muslim scholars such as Afsaruddin must recognize that it is not “Islamophobia” that has brought jihad into public discussion: The global jihadist movement itself is responsible. If there were no self-described jihadists waging self-described jihad against many Muslim-majority states and their Western allies, then the question of jihad would probably be as little discussed as it was prior to 9/11. Muslim scholars such as Afsaruddin could also be more sensitive to the fact that, while their restrictive reading and application of jihad is laudable, it does not illuminate what jihadists believe, which is what policymakers, scholars, and the general public all seek to understand.

Religion

Religion is the Western conceptual category most readily observable in jihadist thought. The term din (religion) occurs frequently and centrally in jihadist literature. Moreover, jihad, as conceived by jihadists, is taken to be a fundamental element of din al-Islam (the religion of Islam). One could argue that, in the jihadist conceptual universe, theopolitical concepts such as caliph, Shari’a, and hukm are properly understood simply as religious, or even more precisely, as Islamic, falling under the rubric of din.

But the category “religion” creates real confusion in the Western context, making it a fraught category for analyzing the global jihadist movement and its violence. The heart of the problem is that religion in the Western context is generally construed as both a plural and generic phenomenon, in the sense that there are multiple religions that share a common essence. The Western view is evident in the preoccupation of Western universities with comparative religion as a research methodology and goal of religious studies, and in the concomitant obsession with identifying and defining the putative transcultural essence of religion.

American academic Kenneth Rose, for example, defines religion as “the human quest to relate to an immaterial dimension of beatitude and deathlessness.”[13] French-American Catholic intellectual René Girard defines religion as “any phenomenon associated with the acts of remembering, commemorating, and perpetuating a unanimity that springs from the murder of a surrogate victim.”[14] These are classic essentialist definitions of religion. The problem is that jihadists believe in one religion alone: Islam. When they employ the term “religion” (din), it has no plural or generic connotations, thus making scholarly definitions of religion marginally useful as analytical frameworks for understanding the global jihadist movement.

It is true that Rose’s and Girard’s definitions of religion could be applied in the broad sense to the global jihadist movement. But the quest for beatitude and deathlessness and commemorating the murder of a surrogate victim is unlikely to help comprehension of the jihadist mindset and agenda. Any profitable investigation of the religious dimension of the global jihadist movement must begin with Islam, not with what the global jihadist movement might share in common with Buddhism.

It is, of course, not illegitimate to investigate whether there might be intrinsic links between religion and violence. But this is a separate question from that of the role of the religion of Islam (din al-Islam) in jihadist thought and action, and conflating the two does not aid an understanding of the latter. The Christian Crusades of the 12th and 13th centuries or the German church’s entanglement with the Third Reich do not illuminate the thought, motivations, and goals of twenty-first-century jihadists. Yet these kinds of issues constantly intrude into discussion of the global jihadist movement.

Conclusion

The false dichotomy of religion vs. politics has long hamstrung analysis and discussion of the West’s conflict with contemporary jihadists. Instead of adhering to this facile and dated paradigm, Western academics, journalists, and policymakers should shed their longstanding denial of the role of Islamic theology in contemporary jihadism. Recognizing that the West confronts a potent “Islamic political theology” in the form of the global jihadist movement will be a first step towards understanding the true nature of one of its most enduring security challenges.

Jonathan Cole holds a Ph.D. in political theology from Charles Sturt University and an MA specializing in Middle Eastern studies from the Australian National University. He has worked as a senior terrorism analyst at the Office of National Assessments and the Australian Signals Directorate

Notes

Taqi ad-Din an-Nabhani, Nidham al-Hukm fi-l-Islam, expanded and revised by Abd al-Qadim Zallum (Hizb at-Tahrir Publications, Online, 2002), pp. 13-14. Qur. 5:44. All English translations of Qur’anic passages are taken from N. J. Dawood, trans., The Koran (London: Penguin Classics, 2006). The word translated here as “unbelievers” (kafirun) is the same word that is often translated as “infidel.”

“Unbelievers” is exchanged for “wrongdoers” (dhalimun) in verse 45 and “ungodly” (fasiqun) in verse 47.

Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, “This Is What God Has Promised,” June 29, 2014.

See, for example, Qur. 2:30, which is also cited in the ISIS proclamation: “This is what God has promised.”

D.F. Wright, “Theology,” in Martin Davie et al., eds., The New Dictionary of Theology: Historical and Systematic, 2nd ed. (Downers Grover, Ill.: IVP Academic, 2016), p. 903.

Jason Blum, “Pragmatism and Naturalism in Religious Studies,” Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 2 (2011), p. 84.

Thomas Hegghammer, “Jihadi-Salafis or Revolutionaries? On Religion and Politics in the Study of Militant Islamism,” in Roel Meijer, ed., Global Salafism: Islam’s New Religious Movement (London: Hurst and Company, 2009), p. 264.

Olivier Roy, “Who Are the New Jihadis,” The Guardian (London), June 5, 2017.

Ibid.

Asma Afsaruddin, “Islamist Militants Carry out Terror, not Jihad,” Religion News Service, June 9, 2017. Sun Tzu, The Art of War (Berkeley: Ulysses Press, 2007), chap. 3:18.

Kenneth Rose, Pluralism: The Future of Religion (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), p. 12. René Girard, Violence and the Sacred (London: Continuum, 2005), p. 333.