U.S. participants in the 1983 conference included (top left to right) Bernard Lewis, Dankwart Rustow, and myself. Soviets included (bottom left to right) Yevgeny Maksimovich Primakov and Vitaliy Vyacheslavovich Naumkin. |

With the Cold War still raging, I joined a group of ten American specialists on the Middle East and related topics who traveled to Moscow in November-December 1983. We met intensively over four days with Soviet counterparts on a strictly confidential basis. It was the most useless academic exercise I’ve ever taken part in.

The teams were headed by Dankwart Rustow of CUNY and Yevgeny Maksimovich Primakov of the Institute of World Economy and International Relations (and in 1998-99 the prime minister of Russia). Distinguished American participants included Bernard Lewis, J.C. Hurwitz, and Gregory Massell; Soviets included Genrich Alexandrovich Trofimenko, Vitaliy Vyacheslavovich Naumkin, and Oleg Vitalevich Kovtunovich. An instructor at Harvard at the time, I was both by far the youngest member of the delegation and the most outspokenly conservative, i.e., anti-Soviet.

Rustow has explained the rationale for the meetings: while Washington and Moscow “had genuine differences, even sharp differences, in the Middle East. ... there seemed to be at least one common interest: not to let a regional conflict in the Middle East escalate into a full nuclear confrontation between the superpowers.” Makes sense; too bad the event did nothing to advance this goal.

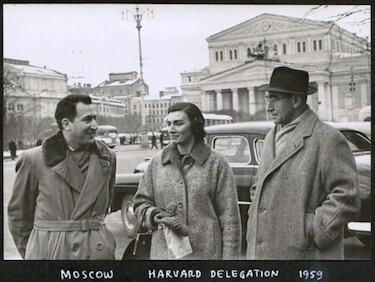

I was not the first in my family to attend an academic meeting in Moscow; my parents, Richard (left) and Irene Pipes, had been there for that purpose almost 25 years earlier. |

I went with eyes open. My father, Richard Pipes, being a professor of Russian history, Communism had been familiar to me since childhood; further, in 1976, I had previously visited the USSR. But joining representatives of the Soviet state on their home territory gave me fresh, first-hand experience.

I wrote a contemporaneous account that I dared not publish because of the emphatic confidentiality of the meetings. However, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the passage of thirty-six years, and the demise of nearly all the participants, this seems like a reasonable moment to go public.

The Account

All went pleasantly enough on arrival in Moscow. Our hosts toasted the meetings to come with the vodka flowing and spoke cheerfully of our getting to know each other, leading to an improved understanding.

The U.S. delegation, funded by the International Research & Exchanges Board, known as IREX, had twice gathered in advance in New York City to work out its position on procedure and agenda; we expected, as is the rule at such meetings, to start the conference by discussing these matters. The Soviet delegation, however, had a different idea. Having unilaterally printed up a schedule detailing the conference program, it intended to preempt this discussion – even as it surreptitiously included more Soviet presentations than American ones.

Our hours of prior consultation were pre-empted by one rapid and clever Soviet move. |

Primakov mumbled at the start of the first session that, unless objections were raised, the program would be accepted as printed. We Americans were still fumbling with the headsets for simultaneous translation and missed this only opportunity to influence the program. Our hours of prior consultation were pre-empted by one rapid and clever Soviet move. It was a sign of things to come.

As Americans, we saw the occasion as an opportunity to offer a range of U.S. viewpoints and explore Soviet opinions. Reflecting this outlook, our papers and presentations were individualistic, analytical, self-critical and low-key. The Reagan Administration, as can be imagined, came in for much criticism and even disparagement. My paper, blandly titled “U.S. and Soviet Roles in the Middle East,” alone defended Washington and criticized Moscow.

The Soviet delegation spoke with one voice and harangued us with strident pro-regime polemics. |

In contrast, the Soviet delegation spoke with one voice and harangued us with assertive and strident pro-regime polemics. Our counterparts consistently echoed each other on every topic – though, admittedly, they tripped over specifics on minor issues (hmm, what’s the current party line on the Egyptian Communist party?). Their speakers looked as diverse as ours in age, gender, and specialization, but they all repeated the same words, ceaselessly and shamelessly propagating the official position.

The Soviets showed themselves to be practiced and effortless liars. Take two examples concerning Afghanistan. First, their expert effusively praised the economic progress there since the communists took over in 1978. He ignored the country’s two million refugees and the powerful mujahidin rebellion against the government. When I raised these topics, he replied that vast amounts of aid drew the refugees to Pakistan; he simply ignored the mujahidin topic.

Some of those Soviet soldiers who “are not now and never have in the past fought in Afghanistan.” |

Second, the same expert dramatically interrupted his own presentation to announce: “As I am confident that none of what I say will leave this room, I can tell you the following fact: Soviet soldiers are not now and never have in the past fought in Afghanistan. They function only as advisors and trainers for the Afghan army.” I am sorry to report that we Americans, being polite and non-confrontational, neither hooted nor laughed, but sat there as though learning something newsworthy and true.

That much was fairly predictable; less so what the Soviets wanted to talk about. Moscow’s activities were simply out of bounds. When I had the audacity to ask Primakov about Soviet intentions in Syria, he exploded, deeming the question out of order, an insult, and an irrelevancy. His anger appeared not spontaneous but a calculated tactic to emphasize that Soviet policy is not suitable for discussion. Indeed, as he wished, Soviet intentions did not once again come up; I felt too isolated by my teammates to try a second time. Indeed, Primakov’s outburst left me feeling unpleasantly vulnerable through the rest of the trip, causing me to keep quieter than usual.

Surprisingly, the Soviets in turn had the good grace not to attack U.S. policies; it sufficed for them repeatedly to quote President Reagan’s March speech about the “evil empire” and to prompt repeated embarrassed American responses.

Rather, Israel was the focus of Soviet abuse. Its policies were termed expansionist, “illegal,” “aggressive,” even “genocidal.” Of all the Russian papers, by far the most virulent was one on the Israeli military. I understood this gambit to explore the possibility of our joining the Soviet anti-Zionist campaign; but if that was the intent, it went precisely nowhere.

There was much high-flying and vague talk about finding ways for Washington and Moscow to cooperate in the Middle East. |

Instead, there was much high-flying and vague talk about finding ways for Washington and Moscow to cooperate in the Middle East. Expressions such as “the friend of my enemy is not necessarily my friend” and “the Middle East is not a zero-sum game” were bandied about. With neither side offering specific proposals, I made a rare intervention, blandly suggesting a U.S.-Soviet ban on exporting weapons to both sides of the Iraq-Iran war and a joint effort to encourage others to follow suit. The Soviet delegation did not deign to address this practical idea.

If we traveled 5,000 miles to be subjected to canned harangues, our consolation was direct exposure to the ruling class of the Soviet Union, to those few who benefit from a failed system. Primakov is an academician (akademik), a member of the nomenklatura, that charmed circle of high salaries, favored apartments, dachas, access to special stores, and foreign travel. The other Soviet participants in the seminar, although also successful and privileged, had a much lower status. This distinction came out daily at lunch when the group divided into three. Other than Primakov, the Soviets ate in the dingy basement of the conference venue; Americans were taxied to a pleasant-enough if dull hotel buffet; and the akademik sped off in his chauffeur-driven limousine to a presumed feast at the academy.

The dreariness of life in Moscow, especially in the approach to the winter solstice, adds to the depressing quality of the conference. Every day is cold and grey, with the sun coming up at about 9am and going down about 3:30pm. The cars we travel in are dirty. The stores are dreary with shelves often empty. The food is heavy and monotonous.

The Rossiya Hotel - massive, drab, and shoddy. |

We were placed in one of the city’s best hotels, the Rossiya, but it is massive, drab, and shoddy. Each floor has its dezhurnaya, the battle-axe who sits by the elevator door and suspiciously watches your comings and goings. Inside the room, the hand shower should fit onto a rod to stay up, but the rod is round and the shower head square. Flushing requires learning how to push and pull the knob repeatedly and just right. The toilet paper resembles newspaper, the soap is laundry-detergent quality, the towels are slightly enlarged dishrags.

I left the seminar deeply displeased by my colleagues. We meekly submitted to the other side setting the terms of the conference, did not ask tough questions, did not pursue follow-up questions, and accepted claptrap as truth. Primakov is an archetypical Soviet bully who tried, with some success, to intimidate me.

What was the point of the exercise? The Americans naïvely hoped to learn; the Soviets stupidly hoped to convince. In short, the whole undertaking completely failed both sides.

Postscript

This was the first of four meetings led by Rustow and Primakov (later ones took place in 1986, 1988, and 1990); unsurprisingly, I was not invited back.

Despite the failure to achieve any of its stated goals, I console myself with the thought that this meeting added one tiny brick to the edifice of Western contact that opened Soviet eyes and that just seven years later helped bring about the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Daniel Pipes is president of the Middle East Forum.