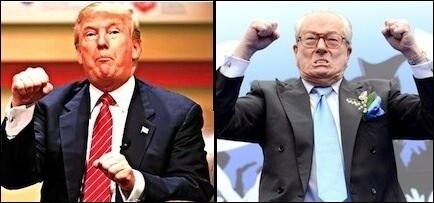

Donald Trump and French far-right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen (right) are consummate showmen who appeal more to an audience’s emotions than to rational argument and debate. |

It is quite tempting to draw parallels between the Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders movements in America and the populist movements that have been rocking European politics for many years. There seems indeed to be, on both sides of the Atlantic, a growing discontent about traditional politics and a feeling among ordinary citizens of being betrayed by a complacent and pathetically incompetent establishment. As a result, we are seeing a swing to both right-wing and left-wing demagogues.

The parallel between Trump and the French far-right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, who founded the French National Front and passed it to his daughter Marine Le Pen in 2011, is particularly insightful. There is a lot in common between both men, as well as some important differences.

Both men turned into political icons quite late in their lives. While Le Pen had been constantly dabbling in politics since his student years, he did not reach a sizable audience until the 1980s when he was almost 60. He became a major player in 2002 at age 74 only when he emerged during the presidential election’s second round -- due to Byzantine ballot regulations -- as the sole challenger of the outgoing conservative president Jacques Chirac. Likewise, Trump may have floated political ambitions since 1988 at least, but he became a serious contender only in 2015 at the age of 69.

Le Pen and Trump turned into political icons quite late in their lives.

Both are “charismatic.” In other words, they are consummate showmen who pay more attention to the audience’s emotions than to rational argument and debate. Le Pen allegedly took lessons with an American televangelist coach, and Trump successfully ran his own reality TV program.

Clearly, their age is more of an asset than a liability in this respect: showmanship means physical energy, and while that may be taken for granted in young men and women, it strikes as magical or superhuman in older men. Think of the Rolling Stones or of French rock singer Johnny Hallyday, well into their seventies, who attract larger crowds than most juvenile rock and pop singers.

Both Le Pen and Trump are truculent, indulge in bad-taste jokes, discard political correctness, and play on racist and sexist themes or innuendoes. Both can be rude towards sick or physically challenged people: Le Pen once suggested that AIDS patients should be locked in special facilities; Trump appeared to mock a disabled New York Times reporter.

Both men indulge in bad-taste jokes and play on racist and sexist themes.

Both project a macho image but have had complex relationships with women. Upon separating from him, Le Pen’s first wife Pierrette, a former pin-up girl, stripped naked in 1987 for the French edition of Playboy magazine. Trump appeared on Playboy‘s cover in 1990 along with playmate Brandi Brandt.

Again, such behavior or such reputation is purportedly counterproductive with many voters, and especially with conservative Christian constituencies. In fact, it is not. The ultimate reason for both men’s rise in polls and electoral returns is that they tackled the taboo of the day: the impact of mass immigration, including Muslim immigration, on society. Being provocative or outlandish on other issues as well is understood as a reassurance to keep a steadfast stand on that main issue.

Le Pen has been constantly recycling the old European far right’s conspiracy fantasies, according to which powerful minorities (Freemasons, Jews, “the System”) are enslaving the common people. Trump draws -- albeit in a softer and less systematic way -- from somewhat similar American traditions, going back to the Know-Nothing Party and Nativism. Le Pen, who stands against the EU and NATO, tends to equate globalization and multiculturalism with American “imperialism.”

Both welcome the rise of nationalism abroad and express affinity for foreign dictators.

There is a growing America First and isolationist element in Trump’s foreign policy views. Both men seem to welcome the rise of nationalism in all parts of the world, including among America’s or the West’s rivals. Both have expressed sympathy, or at least appreciation, for foreign dictators and strongmen. Le Pen, for all his anti-Muslim militancy, was a fan of Saddam Hussein and now worships Putin; Trump expressed negative views about the Second Gulf War and occasionally praises Putin and the Chinese regime.

What about the differences? Both Le Pen and Trump are rich, but millionaire Le Pen is a pauper compared to billionaire Trump. Moreover, Le Pen inherited most of his money from a political supporter under opaque circumstances, while Trump inherited his own money from his father and then expanded it geometrically as a versatile businessman.

Many of Le Pen’s original sympathizers stem from the farthest right – in France, this means Third Reich and Vichy state fans -- whereas Trump, until recently, cultivated as many liberal Democrats as conservative Republicans. Le Pen once attempted to ingratiate himself with the Jewish community in the 1980s, but soon lapsed back into anti-Semitic rhetoric. He has been repeatedly fined or suspended as a member of the European Parliament for anti-Semitic offenses and Holocaust denial (he was just issued a 30,000 euro fine for saying -- again -- that the Nazi gas chambers were “a mere detail” in WWII history). Trump has always been on friendly terms with Jews; he is close to his daughter Ivanka, who converted to Orthodox Judaism and married an Orthodox Jew.

Le Pen has long been an outcast in France, while Trump has been a member of the social elite for decades.

A more marked difference is that Jean-Marie Le Pen has remained a social and political outcast, or at best an outsider, all his life. Although he consolidated his party, the National Front, into France’s third political organization after the conservatives and the socialists in popular votes, he never managed to be a real frontrunner. In the 2002 election, the only time he stood on center stage, he garnered only 18% of the vote against 82% for Chirac. On the contrary, Trump has been for decades a member of the social elite (even if a rough and unpolished one). He was able, once he decided to run for president, to make it as a regular Republican candidate and to take the lead from within in the GOP primaries.

Many French observers wonder whether Le Pen ever nurtured real political ambitions. A prevalent conservative view is that Le Pen’s rise in the 1980s from about 1% of the national vote to more than 10% was largely engineered by the Machiavellian socialist president François Mitterrand to weaken the classic Right and keep a declining Left in power. An alternative view is that Le Pen has been more content to be a cult-like “King of the National Front” than to vie for actual power. A vastly different situation has arisen with the advent of his daughter and heir Marine Le Pen, who seems serious about winning and ready to take the requested steps to this end -- including departing from many far-right topics. A successful approach so far, she has since doubled her father’s scores nationwide.

Trump may be as destructive for American conservatism as Le Pen was for the French Right.

Which brings us to a key question about Trump. Unlike Jean-Marie Le Pen, Trump is clearly running to win. What is going to happen if somebody else wins the Republican primaries or -- to quote his own word -- “steals” the nomination? On March 29, he explicitly revoked an earlier pledge by which all Republican contenders promised to support the nominee that will emerge from the GOP Convention, whoever it is. Chances are, if he does not get the nomination, he will run as an independent candidate and thus help the Democratic candidate -- Hillary Clinton, probably -- to be elected.

If this is indeed the case, Trump may be, even unintentionally, as destructive for the GOP and American conservatism as Jean-Marie Le Pen was for the French Right.

Michel Gurfinkiel, a Shillman-Ginsburg Fellow at the Middle East Forum, is the founder and president of the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute, a conservative think tank in France.